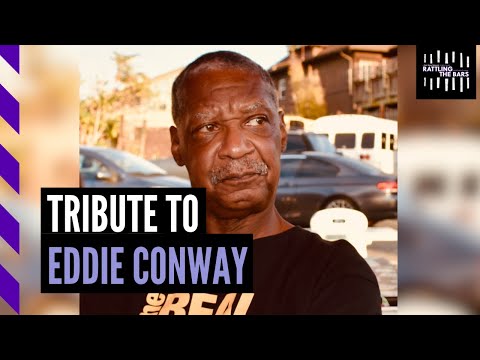

Marshall “Eddie” Conway joined the ancestors on Feb. 13, 2023 after a yearlong battle with illness. Born in Baltimore in 1946, Eddie joined the the Black Panther Party in 1968. The Baltimore BPP chapter, with Eddie’s support and leadership, built strong community ties through efforts like a free breakfast program, a system of robust internal political education, and an increasingly widespread local distribution network for the national BPP newspaper—despite near constant police harassment, and even high-level infiltration of the branch. In 1970 Eddie was framed for the killing of a Baltimore police officer, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison in 1971. He continued to organize for the entirety of his incarceration, which lasted for 44 years until his conviction was overturned in 2014. After his release, Eddie immediately reentered the work of organizing in Baltimore, and joined The Real News as the host of Rattling the Bars. In this special tribute video, Eddie’s family, friends, comrades, and coworkers look back on his life and the ways he touched us all as individuals and the wider world.

You can read a written tribute to Eddie Conway from The Real News here.

Studio Production: Cameron Granadino, David Hebden

Post-Production: Cameron Granadino

Transcript

Mansa Musa: Welcome to this edition of Rattling the Bars. I’m Mansa Musa.

Maximillian Alvarez: And I’m Maximilian Alvarez, editor-in-chief here at The Real News Network.

As you all know, last month on Feb. 13, our comrade, colleague, friend, and mentor Marshall Eddie Conway joined the ancestors surrounded by friends and loved ones. There’s really no way that we can sum up how much Eddie meant to us here at The Real News and beyond. His loss is, frankly, incalculable. And for the past month, we have been grieving Eddie’s loss, but we’ve also been talking amongst ourselves, me talking with Mansa, Mansa talking with Eddie’s family and the rest of our staff. And we’ve really been trying to take stock of what a gift it was to know Eddie and work with Eddie and be influenced by him and his incredible revolutionary heart. And we want to continue that for Rattling the Bars, the show that Eddie himself founded after being released from prison where he was unjustly incarcerated for 44 years after being framed and wrongfully imprisoned in 1971 without proper legal representation.

Again, there’s so much that we could say about Eddie Conway and so much that you all know, I’m sure, from watching this incredible show, which we are now honored to have Mansa Musa hosting every week. But we thought it was important on top of live streaming the memorial service for Eddie – Which you all can watch on The Real News Network channel. If you go to our past livestream section, you can see the memorial service for Eddie, where Mansa himself, along with a number of other comrades, family members, and loved ones, gave really beautiful tributes to Eddie. You can go watch that anytime that you want.

But here on Rattling the Bars, we wanted to make some space to reflect on Eddie’s life and legacy and how that legacy has touched all of us and how we are going to carry on his fight as we know he would want us to. And so in that vein, Mansa, I’m really honored to be on the show with you today, man. And I just wanted to first say what an incredible honor it’s been to have you come on the show. I know that it really meant a lot to Eddie to have you take over the hosting duties, and you’ve really done incredible things with the show. So first, I just want to say what a pleasure it’s been to work with you, brother.

Mansa Musa: And I appreciate that. I think I told Kayla last time I was down here that she was a wonderful host, but that was my sentiment for the entire Real News staff. You all welcomed me on Eddie’s word. It would’ve made a difference if you all would say no. It would’ve made a difference because you all have a voice in this matter. But I’m confident that he chose me because he thought I would be capable of meeting the standard that The Real News had set, more so than bringing a friend on. But putting me in a space where I would keep the standard alive. And I’m thankful that I’ve been able to make a small contribution.

Maximillian Alvarez: Hell yeah, man. I think the contribution has been incredible. And yeah, I think it’s just been such a beautiful thing to watch. Obviously for the past year we’ve known that Eddie’s been fighting valiantly to recover in the hospital, and we’ve been sending nothing but love and solidarity to him, to his wife, Dominique, to their family and friends, hoping that he would make a full recovery. But obviously the ancestors wanted him back, and who are we to deny them their Eddie?

But I think that, over the past year, seeing how you have taken that responsibility of carrying on this show that Eddie believed in so much, carrying on the purpose of that show and the humanity in that show, but also making it your own, really letting more of yourself come through in the interviews and getting more comfortable with the interview style. It’s just been a real pleasure to watch.

And that was actually one of the reasons that I wanted to sit down and have this chat, because we recently published an incredible interview that you did for Rattling the Bars. It was our Malcolm X episode that we published on the anniversary of his assassination. And I feel like I got to see a different side of you in that interview. Well, I kind of saw it when you came on my podcast, Working People, and we talked a bit more about your political trajectory. And then when you were doing that interview for Rattling the Bars a couple weeks ago, I heard you talking about being in the prison yard with Eddie and other folks on the inside, flipping over these milk crates with your little red books and talking about radical political theory, organizing, raising your own consciousnesses in the most hopeless of places. And I was like, man, I want to know more about that.

So before we get to that, for folks who watch you every week, who tune into Rattling the Bars, who knew Eddie and now know you, I was wondering if we could let them know a little bit more, and if you could talk a little bit about how you came to know Eddie Conway. Who were you when you came into the prison system and met Eddie? What was that like? What kind of conversations did you guys get into?

Mansa Musa: And that’s very interesting, Max, because when I came into the prison, I had just received a life sentence in Maryland Penitentiary. I got convicted of a crime that involved the police. I knew that my situation, at best, I was going to be in prison for a long time. And so immediately, while I was in the county jail, I started reading and becoming more aware of the social conditions that Black people was in, and poor people in general.

When I got into the Maryland Penitentiary, I came into Maryland Penitentiary Feb. 29 of ’73. March 28 of ’73, they had a riot. The following day I got locked up, beat up a little bit, and put on lockup. So for about 30 days I was on lockup, and then they let me out in the population. And the whole entire time I was on lockup, they was Eddie and the Collective, they was aware where I was at, and they was monitoring what was going on with me. But that was unbeknownst to me.

So when I got out, I had a comrade named Tohanka – Who, by the way, has served over 51 years. We trying to get him out now. He approached me and told me about the collective, had a group called Maryland Pen Intercommunal Survival Collective, which was a hybrid of the Black Panther Party. And asked me, did I want to be a part? I said, yeah. So he introduced me to Eddie.

But in terms of Eddie, Eddie is not a person that when you come in contact with, you don’t feel like you in the presence of royalty. You just feel like, hey, what’s up man? He that kind of person. But more importantly, his encounter with me and his engagement, we was like, where you at? Where you sleeping at? How you doing? What’s the situation? What’s your plans? And trying to get a general understanding of what my thinking was.

And so I told him, I’m trying to get out of prison. Right now I don’t really know too much about prison, and I don’t have no problem being a part of the collective. So he said, okay, well what you want to do in it? So I said, well, anything. He said, okay, we got a library. He said, we got these books in different comrade’s cells, make sure you get all the books and put a list together of all the books.

Maximillian Alvarez: Eddie assigned you a reading list [laughs].

Mansa Musa: A reading list, automatically. So I get all the books, gather them all together. But I’m dragging and procrastinating about putting the list together. He wait about four or five days, say like, you got the list? Like, no, man. This first time I’ve been out and being able to rip and run, so I’m doing a lot of other things like playing basketball, stuff that I like to do that I couldn’t do in the county jail.

But what happened was, because I took that library and we were just starting to organize our classes, because on the heels of that riot, they had just let the population back out. So by the time I got back in population, the general population was just getting back out. Maybe it had been out a month prior to me coming out, so they wasn’t allowed to be together either. That’s when we started. We had got together and decided they were going to create our classes. We had a series of classes that we would attend: political education, guerilla warfare, first aid, stuff like that to make us aware of what’s going on and prepare us.

And so we’re having a political education class. He said, well look, you going to teach the first political education class when we resume. And I’m like, well, what is that? [Max laughs] What is a political education class? And so that led us to going, and every day we were going to the bleachers with the red book. And we went through the whole on contradiction in the red book. And he explained what dialectical materialism is, what contradiction is. But more importantly, he explained it in the context of looking at it in a society perspective, the contradiction between the have and the have-nots.

The fact that if you have a situation where your subjective conditions, meaning your organization, your subjective conditions in your organization might not be commensurable with the objective condition. You go out and say like, well, we going to plan to have a strike. We want to organize a strike as an organization. But subjectively, internally, everybody’s scared of the masses. When you say, okay, go out, pass out literature, pass out pamphlets in the most depressed areas, the people don’t do it. Then when you come calling a strike, ain’t nobody out there but you and somebody else. He was explaining that when you organize, you have to make sure your internal is commensurable with your external. Your internal, which is your organization, is educated enough to be able to effectively organize people.

And this is what he bestowed on me, that sense of understanding that, okay, no matter what, when you talking about organizing, make sure that you understand that principle. Don’t think the fact that you have a lot of rhetoric, that people being very rhetorical, people angry, that’s going to convert into being effective in terms of changing the narrative. That’s only going to be effective in terms of making people feel good at that moment. But when they leave out of there, what are they going to do?

Maximillian Alvarez: I think it’s such a critical tool for any organizer to learn. It’s not just about knowing all the theory or even all the history. You have to be able to understand how people work, including yourself. And you’ve got to start by understanding yourself and how you feel and why you feel that way and how you became the person you are. And then from there you can engage more thoughtfully and successfully in the art of mobilizing people.

And I wanted to pause on that for a second, because this is something you and I spoke about when we talked on my show, Working People. You mentioned the importance of raising your own consciousness when you were incarcerated, and how that was not only a life-saving thing, because if you’re not working on that and you’re in the most horrible hopeless place imaginable, eventually everyone is going to get eaten alive if they’re not working on something like that. They’re not working on raising consciousness and organizing their fellow prisoners and even trying to organize and make those connections beyond the prison walls. And so we’re going to get to that in a second.

But I wanted to ask what it meant to you to get into those conversations, to read those books, to think about that. Because you grew up in a very segregated Washington, DC, in a very segregated America. Black people were very much second-class citizens, and the white establishment made sure that you knew it every step of the way. What did learning that type of politics and political theory, what did it mean for you personally at that moment in your life?

Mansa Musa: See then it gave you purpose, because now you understand who you are in relation to society, more so than being in a reaction to society. Now you understand that you have the power and ability to change conditions, because you’ve got a method of thinking that’s going to allow you to understand the phenomena, those conditions that you are confronted with and how to be effective in changing. And that’s what it meant to me.

It opened my eyes up to the point that I understood that if I continue to educate myself, if I continue to stay relevant in terms of information, if I continue to be analytical in terms of what’s going on in the world, if I make the connection between, as Malcolm was doing, when Malcolm talking about he had an international perspective, but he was talking about when he made his international analysis, he was saying that, oh, it’s all capitalism and imperialism.

If you look at it only as the United States and not the United States as being responsible for during the time when Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Tanzania, you don’t look at them in terms of how imperialist power is destroying countries abroad – Vietnam – Then we always going to be looking in isolation and looking at things in a real myopic view. It gave me a broad perspective.

And to reflect back on Eddie, because the thing with Eddie was, you having a conversation with Eddie, he’s an astute political thinker. You having a conversation with him, he not looking at you like, oh, I can outthink you. I know more about this. He actually talking to you to get you to understand how to develop your thinking. His conversation with you is he asking you questions to get you to figure something out about a particular thing to see what more I got to do to you to get you to understand this so that you can be the person that you need to be to go forth and move this narrative?

His conversation, he might come up and say like, well, why do you think Malcolm and King didn’t get along? Or, what was the problem between them? In his mind, he always saying it wasn’t that they didn’t get along, it was just that they had two different perspectives of social conditions. Or then he might come back and ask you, who do you think was more effective in that? That’s where everybody would say Malcolm, but the reality was King. Because who was more effective in terms of creating an organization that changed the Montgomery bus boycott, that had people dismantle the institution?

But he wants you to see where you at. So once you go and say Malcolm, then he going to dial in on you, why? And all your conversation going into his rhetoric. And not saying that Malcolm, his oratory skills and his educational skills wasn’t valuable, but when they were converted into practicality, he died before he had a chance. Because when he came with OAU, he started to set up a political platform. King and them had already did the march on Washington, Poor People’s Campaign. They was organizing the South. They was doing a lot of things. And Eddie would have you in that conversation.

Then you might argue with him for a week on end, and he’ll start throwing more and more stuff at you. Like, but have you read this book? Go back and read this and tell me how that fit into your analysis. And at the end you be like, man, yeah, he right. And he won’t tell you that I agree with King. He won’t say, I disagree with Malcolm. He’ll just be letting you know that in making an analysis, how you make your analysis, your analysis might be converted into an application. That’s the goal. Your analysis, you’re not being an armchair revolutionary. You’re not being like Dr. King say, a paralysis of analysis. You’re not making a paralysis of analysis. You’re actually saying, okay, this is the problem, why. This is the solution. How we going to implement this in this particular situation that we find? We going to phase it in like this.

And that was the thing about Eddie. Everybody that I know that dealt with him, made all our comrades that was educated by him or respond to him, all of us thought the same way. And those of us that couldn’t cut the mustard, they just didn’t participate. But those of us that could cut the mustard, as we got older and migrated out to different institutions… You knew that we was in them institutions because when you come in there, first thing they say, oh, who in here? Say, Mansa. Oh, what Mansa doing? Because they know you organize. They know you got some kind of program, some kind of project, something going on that got people involved, and you got access to resources that can get the population involved. They would be like, Mansa man, look, I know you doing something. I know you got some kind of function going on. You got people coming in, you got some kind of… Because that’s what we was left with.

Maximillian Alvarez: And I mean, it’s weird to smile hearing that. Because again, we’re talking about a prison-industrial complex that is itself an inhumane institution of violence that is meant to swallow and destroy people. It’s not meant to rehabilitate anybody. It’s meant to destroy people. And that’s what it does, sadly, to so many.

But to even think that in those sorts of conditions, that they couldn’t kill the spirit of the Panthers. They couldn’t kill the spirit of revolutionary thought. And whether that be with Eddie and you all and the Maryland Penitentiary, or like you said, then you travel out like spores to these other institutions and you bring other folks in. You had those conversations and reading those same texts and seeing that ripple effect. That’s what really hit me at Eddie’s memorial. Because I was feeling so self-pitying and lamenting all the conversations that I didn’t get to have with him and would never get the chance to have.

I mean, at Eddie’s memorial, that was the first time I ever met him in person. Because during COVID, after 44 years in prison, Eddie had to be on lockdown because of all the damage that prison had done to his body. Before we had the vaccines, I was just working with him remotely, but I feel like I still got to know him very well.

But anyway, up until his memorial, I was thinking about all the things I wanted to ask him or talk to him about but now I wouldn’t get to. And then I just heard all the other people tell their stories about him. And I feel like that was me having those conversations.

Mansa Musa: Exactly, exactly.

Maximillian Alvarez: I got to learn everything I wanted to about Eddie through all the people whose lives he had touched, including you. And I think that’s a sign of a truly great organizer and teacher, what you said. And that’s something that we all recognized in Eddie. Someone at the memorial said a line that really caught my ear where they said, Eddie saw the light in people before we even saw it in ourselves.

Mansa Musa: Yeah. And that’s an accurate description. Salim al-Amin said when he came in and I seen him. We was talking. He’s a devout Muslim. And first thing he said, oh yeah. He said, that’s where I got my political education from. Because that’s what Eddie did.

See, like the brother spoke about being a Muslim, Eddie didn’t say, don’t be a Muslim. Eddie say, what you believe in, how is it helping your people? How is it bettering your environment? How is it bettering the conditions of your people? If it ain’t bettering the conditions of your people, you might need to reevaluate that.

Because we was talking about Jeff Bezos, now you are in a position where you are starting to look at yourself in the same light as a blood sucker. So you don’t have no relationship with your people, or you don’t have no connection with oppressed people. You don’t feel like the conditions that your family’s in is a problem for you, something wrong with your thinking.

Maximillian Alvarez: Yeah, yeah. No, I think it’s such a great way to put that. And again, the thing that I think makes Eddie and you and everyone who’s involved in that such an effective organizer is because you ultimately recognize that other people have to walk through that door themselves. Like you said, you can’t just talk at people, you can’t control people to think the way you want them to think. You have to respect their agency as a human being and as an individual who has to go through their own struggle of developing consciousness.

There’s a real profound respect for other people in that way. I’m asking those questions, but you’re the one who has to respond to them. You’re the one who has to think these things through and then tell me what you came up with. And I think that’s a lesson that Eddie taught me that I try to carry on in the work that I do when I talk to workers. I never, ever, ever want to talk down to anyone, never act like I know more than they do. Just try to be eye to eye with people and talk amongst ourselves as fellow human beings who all have our own struggles, but who are all part of the larger struggle together.

And I guess on that note, maybe to round things out, I wanted to think about what that means in the larger historical context. That you and Eddie, you’re chapters of that history. I think a lot of folks in my generation, especially those who are on the left, sadly can forget when we talk about like, oh, what happened to the left in the United States or in the West after 1968? And so we’ll talk about where the radicals, predominantly the white radicals of the student movement, so on and so forth, what happened to them?

And we forget that an entire chunk of the radical left was either assassinated or imprisoned. And we’re talking about some of the most dedicated revolutionaries like Eddie Conway. And we forget that the system actually attacked the people it saw as the greatest threat to its hegemony and swallowed them into the prison-industrial complex. Eddie has a great line in one of his books where he’s like, the moment Black people started rising up and demanding accountability from a white supremacist system in the form of the Civil Rights Movement, the Black Power movement, that’s when the prison started swelling with Black bodies. It was a clear reaction. The boom of the prison-industrial complex was a reaction from white supremacist, capitalist society to take in those threats.

And yet, even in the guts of the prison-industrial complex, you guys wouldn’t shut up. You wouldn’t go away. You were still organizing. You were still thinking and raising consciousness and putting on conferences in the prison and organizing labor unions.

And even not just that, if it’s not at that grand of a level, just helping other brothers, sisters in different institutions not lose themselves. Again, that was what stood out to me at Eddie’s memorial. There’s so many people, even like yourself, who could have gone another way. But because you got into this collective, you got into this conversation, you got invested in that struggle, you didn’t go that other way.

And so I wanted to ask for folks watching and listening who maybe don’t understand the significance of what you and Eddie and your generation of radicals, what it really means that you all were swallowed up by the prison-industrial complex but used that time still to organize. What do you think people should know about that?

Mansa Musa: Just this is the reality. Fascism, capitalism, and racism, they use fascist tactics. Same way the Gestapo where Hitler had the Gestapo round people up and put them in concentration camps. Well, they used that. When they rounded up and killed, like you say, the ones they didn’t kill they rounded up and put them in prison. But what they did in doing that, these elements, these revolutionaries, these nationalists, these civil rights activists, when they come in, they come over with a different discipline.

They don’t come into prison and say, old food, bad. We going to accept it where a person have a criminal mentality, that doesn’t know recidivism, they’re accustomed to it. They come in and find their niche, their comfortability and accept the conditions as they are. But when you start putting that other element in there, that was putting a fuse in the dynamite. Because now you got somebody that’s going to say, oh, no food’s bad. Food ain’t supposed to be bad. Food’s supposed to be better and we got to do something about it.

And when they say, well, what you going to do about it? Say, we not going to go in the kitchen and eat, and we going to make them give us better food. And so now, a person that might not have a propensity to be a radical or organizer or just want to do his time and get by. But now when they say, man, don’t go in the kitchen. And he see that the food then changes, say, oh, that’s all it took was for me to stand up?

This is when you put Panthers in the prison system, they got people, I think like Dr. King say, straighten your back up. They got people to straighten their back up and start saying, no, we are not going to tolerate inhumane living conditions no matter what you say or why we are here. And as a result of that, they became more political.

John Cliche, [inaudible], George Jackson, they wasn’t revolutionaries when they came into the system. They became politicized in the system as a result of other people that came in and they was exposed to… Comrade George even mentioned being exposed to certain people that raised his consciousness.

Eddie Conway, the people that was in our collective with us, none of us was former Panthers. Most were petty criminals or criminals in our own right. But when we got exposed to Eddie Conway and then Conway educated us to understand that our way of looking at things is wrong on all levels. And unless we change, we going to continue to be in the state that we in. But if we change, we might not live, but we will leave a legacy of making changes.

That’s what people need to take away from this is that when you look at what the sentencing project is doing there called 50 Years and Wake Up. They saying expanding the prison-industrial complex started 50 years ago, so this is the anniversary of it, and they’re doing a series of things in terms of educating people. The point, within that 50 years, the ’60s when they started locking Panthers up, when they started locking the militants up, when they started locking members of the Republic of New Africa up, when they locked up Ben Chavis and the Wilmington Ten, when they locked them up.

When them institutions they went in, they went in them institutions, and they went in the institutions thinking that, I know who the enemy is and I know that this is just a part of the process, and I still have to fight. I’m not going to fight. I’m going to organize in here. I’m going to make people aware of what’s going on here. These are the masses that I have exposure to right now, this prison population. I’m going to take these masses of people. I’m not going to say, well, oh, the masses on the outside of the wall, so until I get out, organizing on suspension. No, these are the people. I got to change this thinking. If I can change this thinking and make these guys, and get these guys and women to understand their place, then they going to change.

And that’s what you see now. When you see a person like myself and the fact that Eddie bestowed this on me to be a part of this process, that wasn’t by happenstance. He knew what he created. And he knew when he seen me when I got out. His wife told me – And we laugh about this – She said, all he would say is, man, if Mansa can just get out. Because he knew I might go in the Guinness Book of World Records for the most failed attempted escapes [Max laughs].

And so he knew I had this thing with me. He was like, if he just get out. Because he knew that once I got out and he exposed me to what we were doing, the work that we were doing, then he knew I would find my place because I was educated to be a part of the process.

Maximillian Alvarez: Hell yeah, man. Well, again, we are honored to have you part of The Real News team. You’re doing incredible work here, brother. And yeah, I think we got a lot more work to do. And as much as our hearts are broken with Eddie leaving us, I know that Eddie would be the first person to say, don’t mourn; organize.

Mansa Musa: Yeah, yeah, exactly.

Maximillian Alvarez: We gotta get back to work.

Mansa Musa: Exactly.

Maximillian Alvarez: I guess in that vein, I just wanted to ask if you had any final words you wanted to share with your audience about how we’re going to carry on Eddie’s legacy? Or what lessons they should sit with and take into their own lives.

Mansa Musa: Eddie created Rattling the Bars to be the voice of the voiceless. And in turn, Rattling the Bars come from when we was locked up in South Wayne and the most hardiest, treacherous, inhumane part of the prison. And in order to get the attention of the guards when something happened, somebody was sick, we would rattle the bars and beat on the bar. We’d make so much noise they had to respond.

The symbolism of that is that George called the grumbling of our feet. The symbolism of that is that we are asking you to continue to support Rattling the Bars. That’s what Eddie would want, for you to support this, to critique this, to offer your suggestion, to offer your criticism so that we can make this better.

Because this is your voice. It’s the voice of the voices, and this is what The Real News represents. It’s not called The Real News by happenstance. It really is the real news. And we want you all to continue to support us. That’s what Eddie will want, and that’s what I’m asking. I’m asking you to be patient with me as I go through this process, but more importantly, I’m asking you to listen to what we are doing, support what we are doing, and be a part of this process.

Maximillian Alvarez: Thank you so much for watching The Real News Network, where we lift up the voices, stories and struggles that you care about most. And we need your help to keep doing this work, so please tap your screen now, subscribe, and donate to The Real News Network. Solidarity forever.