Transcript

Jaisal Noor: The coronavirus now has one in four Americans living in lockdown.

Almost 100,000 small businesses permanently closed since the pandemic.

Vinny Green: We lost 70% of all our accounts.

Jaisal Noor: When the pandemic hit, Baltimore rallied behind Taharka Brothers Ice Cream.

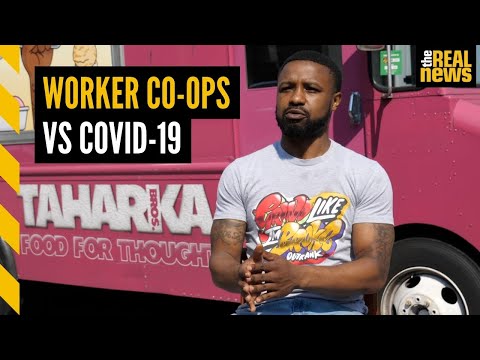

Detric McCoy: Baltimore, Maryland, saved Taharka Brothers tenfold. And I love that the city did that for us. And you know, I believe they did that because of what we do here.

Jaisal Noor: At the majority Black-owned Taharka Brothers, it’s about more than just ice cream.

Detric McCoy: You got guys all from poor neighborhoods, right, and we probably should die according to the statistics. But because we have an opportunity to become owners and some of us are owners, that we appreciate our lives, we appreciate our jobs.

Jaisal Noor: Launched in 2010, Taharka Brothers gained popularity by empowering young men of color with decent paying jobs and leadership building opportunities making ice cream. After a lengthy transition in December of 2020, Taharka Brothers became just the latest local business to convert to worker ownership.

Vinny Green: We have some of the young guys in here, Deon and Kevin, they are managers in the kitchen, they help produce all the ice cream and help create a lot of the flavors and we have flavor committees where the team can come up with a lot of different amazing flavors… Worker co-ops, it changed the solution so much, giving the gratitude that the employees can actually feel ownership, to know their hard work does not go unnoticed. And then it makes you want to do better for yourself no matter what, whatever the obstacle is set around your surroundings.

Jaisal Noor: Working at a co-op won’t make you wealthy overnight.

Detric McCoy: Everyone always thinks it makes everyone rich. That’s not the case.

Jaisal Noor: And it’s often more demanding than a typical job.

Detric McCoy: Everyone still has to work really hard to get what you want, what you think you deserve. You know, just because I’m a owner doesn’t mean I’m riding in flashy cars. There’s six owners, and it’s more of a responsibility.

Jaisal Noor: In industries rife with low pay and harsh working conditions, co-ops offer democratic workplaces and often better pay and benefits. Taharka Brothers’ 14 workers who are not owners take part in profit sharing, and are offered a path to ownership.

Detric McCoy: We have an advantage of treating everyone fair, you know, and that comes out in our product, which is why I believe our product is so good because we give everyone an opportunity to become an owner, to speak their mind, be a part of committees, go out and get education, get healthcare, things like that. It really makes them feel like ‘Oh man, I gotta make each pint so special. Each tub of ice cream that goes to any restaurant or wherever it goes, it’s going to be the best tub is also going to have my name on it.’ And it does.

Jaisal Noor: So when the pandemic brought hardship, the workers were ready to adapt.

Vinny Green: We lost 70% of all our accounts. We had to make a business pivot. We started a home delivery system, which kept the business alive. Without home deliveries, a lot of our guys would have lost their jobs.

Jaisal Noor: It wasn’t easy to uproot their entire business model.

Vinny Green: It literally was just all hands on deck. All the owners are doing deliveries late at night, coming in the morning early to put all the pints up in the freezer, or just be able to give an extra hand with packing orders or giving assistance wherever it’s needed.

Jaisal Noor: That Taharka Brothers survived a pandemic that laid ruin to so many other small businesses like theirs offers insight into a bigger trend. Although comprehensive data is not yet available, a survey of 140 co-ops across the country suggests that instead of simply closing down, co-ops were able to harness their collective decision-making to adapt their businesses and avoid layoffs. But collective decision-making—at Taharka Brothers, each of the six worker-owners has voting power—can also limit how quickly a co-op can act.

Vinny Green: We make all our decisions as a group. And we all try to make decisions that we can all benefit out of, that we all can agree on, and all think that it’s the right decision for all of us.

Detric McCoy: But the hardest part of it is probably trying to do things in a timely fashion. Especially when we’re in a flavor committee and we’re just sitting back eating ice cream for a couple hours.

Jaisal Noor: But the biggest limitation co-ops face is a lack of access to capital. Racist public policies robbed Black communities of wealth and wealth building opportunities for generations, and co-ops typically don’t qualify for bank loans because they require collateral or personal guarantees that are incompatible with the cooperative structure. For years, Taharka Brothers struggled to raise investment. In 2013, they resorted to crowdfunding to raise money for a new ice cream truck.

Devon Brown: We’re trying to launch this food truck for our Vehicles for Change truck and we need your help to make it happen, to take our business to the next level.

Vinny Green: Taharka Brothers’ ice cream is handcrafted, so we’re gonna handcraft this truck. Yeah, we’re gonna paint this whole truck electric pink, just like my shirt, Taharka Brothers.

Jaisal Noor: They hit their fundraising goal, but needed a more sustainable model. So in 2016 when their ice cream truck broke down, they received a $15,000 loan from BRED or the Baltimore Roundtable for Economic Democracy, a then brand new organization just launched to provide local co-ops with technical and financial assistance unavailable anywhere else.

Detric McCoy: They let us know how it works to be a co-op, what things do you have to do? What’s going to be different from becoming, from worker to now owner, making budgets for your department, helping us out with loans for specific, more equipment or more marketing things.

Jaisal Noor: BRED is part of Seed Commons, a $25 million loan fund that spans 26 cities.

Kate Khatib: So we don’t take personal guarantees. We don’t look at personal credit. We don’t take collateral interests in businesses other than the equipment that’s purchased with the loans.

Jaisal Noor: This helps co-ops become more sustainable, and gives them structures that help them weather crises. None of the 60 co-ops that Seed Commons currently lends to have closed permanently due to the pandemic.

Kate Khatib: And that’s not to say that those businesses haven’t had to shut down, it’s not to say that workers haven’t been temporarily laid off, but it is the case that every single one of those businesses that we’ve invested in has found a way to pivot, has found a way to come back from the pandemic, is continuing to operate, is continuing to provide that access to quality, sustainable jobs with dignity.

Jaisal Noor: A 2015 Harvard study ranked Baltimore among the worst cities in terms of social mobility for African American youth. Two out of three Black Baltimore residents face liquid asset poverty. And African Americans continue to face massive wealth and income gaps and disproportionate rates of arrest and incarceration. Co-ops alone can’t fix this. But worker-owners say they can be part of the solution.

Detric McCoy: I think it would definitely help our community, especially here in Baltimore, if people have something that they can work for, and that they own, and that they can appreciate, but if there were more worker co-ops, I believe there would be more people to you know, fighting for what they believe in and the violence and everything will probably come down a fair amount.

Jaisal Noor: This story was supported by a grant from Solutions Journalism Network, and is part of a series exploring how co-ops across the country have weathered COVID-19. With Cameron Granadino, this is Jaisal Noor.

Taharka Brothers is about more than just ice cream. They are a worker-run business that provides living-wage jobs, leadership, and wealth-building opportunities to young people of color in a city that offers few pathways to success. So when the pandemic hit, they were ready to pivot their business model, and stayed running at a time when so many others were forced to close permanently. Worker-owner Detric McCoy told TRNN’s Jaisal Noor: “Baltimore, Maryland, saved Taharka Brothers tenfold. And I love that the city did that for us. And you know, I believe they did that because of what we do here.”

This story has been supported by the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.

Tune in on May 13 at 7PM EDT for the premiere of our full special report on worker co-ops and the COVID-19 pandemic, followed by a live Q&A, co-sponsored by the US Federation of Worker Cooperatives and the New Economy Coalition, featuring worker-owners from cooperatives across the country, and moderated by The Real News’ Managing Editor Lisa Snowden-McCray.

Kate Khatib, co-founder and co-director of Seed Commons and executive director of BRED, is the spouse of TRNN Executive Director John Duda.

Studio/Post Production: Cameron Granadino