Arkansas resident Shawn Chaperone was cut off by a reckless driver and was shocked that police chose to pull him over. However, it was the local police department’s turn to be surprised when they discovered how well Shawn knew his rights and local ordinances! Join us for this episode of the Police Accountability Report, which illustrates the importance of knowing your rights and the dangers of arbitrary police power.

Production: Stephen Janis, Taya Graham

Post-Production: Stephen Janis, Adam Coley

Transcript

The following is a rushed transcript and may contain errors. A proofread version will be made available as soon as possible.

Taya Graham:

Hello, my name is Taya Graham and welcome to the Police Accountability Report. As I always make clear, this show has a single purpose: holding the politically powerful institution of policing accountable. And to do so, we don’t just focus on the bad behavior of individual cops. Instead, we examine the system that makes bad policing possible. And today, we will achieve that goal by showing you this video of a cop who tries to entrap a motorist with false accusations about a costly traffic violation. However, it’s how this driver fought back, and how police responded when he did, that shows how cops can bend the law when they’re caught misusing it.

But before we get started, I want you to know that if you have video evidence of police misconduct, please email it to us privately at par@therealnews.com, or reach out to me at Facebook or Twitter @TayasBaltimore, and we might be able to investigate for you. And also please like share and comment on our videos. It helps us get the word out and can even help our guests. And of course, I read your comments and appreciate them. You see those hearts down there. And we do have a Patreon, Accountability Reports. So if you feel inspired to donate, please do. We don’t run ads or take corporate dollars, so anything you can spare is truly appreciated.

All right, we’ve gotten that out of the way. Now, as we’ve reported on this show, there was no process more fraught with potential for both abuse and overreach than the American traffic stop. It is in some ways unique to our American version of law enforcement, simply because cops here think there is no better way to catch criminals than by randomly pulling over hundreds of people. How else can you explain the myriad of stops we have reported on for this show that have led to, let’s just say, bad outcomes, unnecessary and often futile efforts to entangle innocent Americans in our sprawling criminal justice system that often seems more motivated by greed, stupidity, or even just a hunger for power? And to prove my point, I’m going to show you this video of a traffic stop that explains all the preceding overreach and backwards rationalizations that American police use to justify their addiction to lighting up the roof and ensnaring often innocent motorists in the labyrinth system of tickets, fines, court fees, and more.

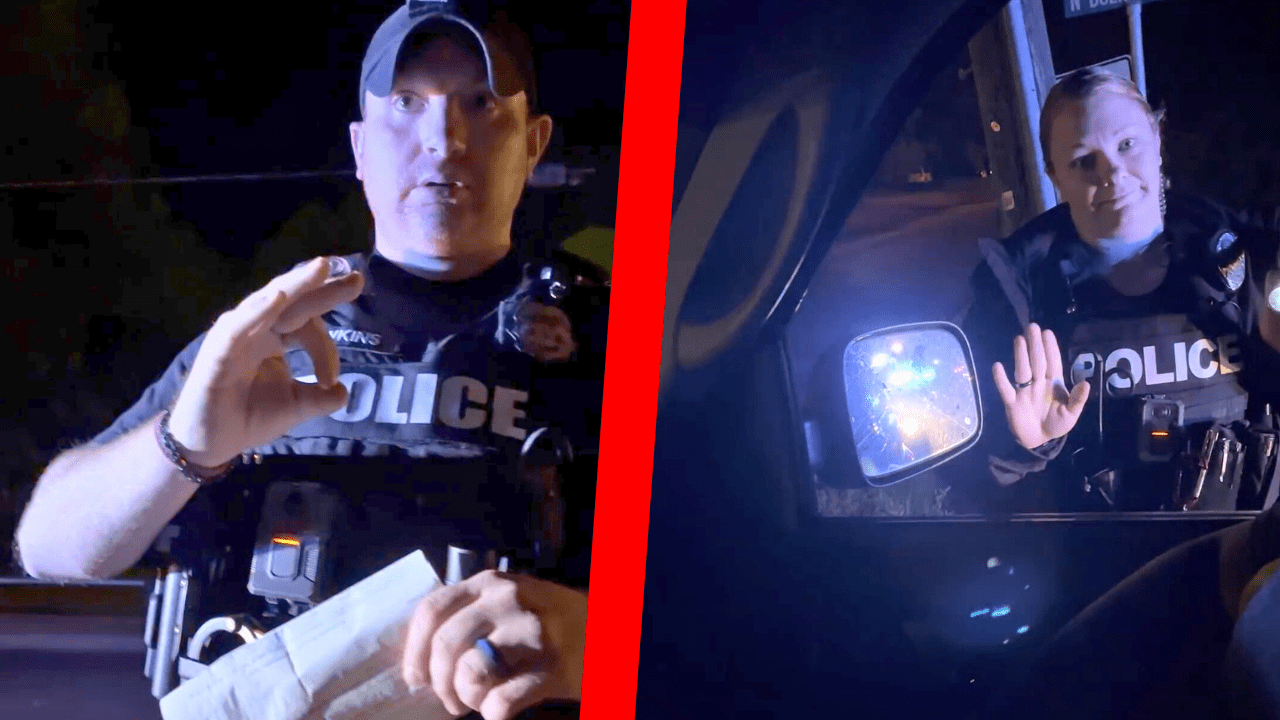

But this take on over policing also has a twist, which you’ll see leads to an even more revealing truism about law enforcement’s addiction to traffic stops than all the aforementioned incidents combined. Now, this story starts in Stuttgart, Arkansas. There, Sean Chaperone was driving home after a long day at work. He was traveling at the reasonable speed of 35 miles per hour, when suddenly a motorist jumped in front of his car, slowed to 20 miles per hour, slammed on their brakes, and cut him off. Now, Sean did what any driver would do when confronted with a reckless motorist, he switched into the next lane to avoid a collision and maintained his speed. But this seemingly reasonable reaction to a reckless motorist apparently caught the eye of the ever vigilant Stuttgart Police. This laser-like attention was not drawn to the driver who cut Sean off. No, these able practitioners of law enforcement where apparently focused on the fact he changed lanes to avoid an accident. Just watch.

Sean Chaperone:

So he’s behind me, but you couldn’t catch him, but you could catch me?

Speaker 3:

This is what I seen. I seen you slam on your brakes and come to a sliding stop in the middle of-

Sean Chaperone:

That is correct because he cut me off, sir.

Speaker 3:

Listen to me. Listen to me. Listen to me. First of all, I’m not going to roadside court. Second of all, your attitude, you should probably lose it right now. Do you understand?

Sean Chaperone:

Or what?

Speaker 3:

Do you understand?

Sean Chaperone:

Or what do you going to do, man?

Speaker 3:

It is a simple yes or no.

Sean Chaperone:

I don’t answer questions, man. You go do what you got to do.

Speaker 3:

All right.

Taya Graham:

Now, it’s interesting to note that this alleged traffic infraction caught the attention of not one, not two, but three Stuttgart cops, a veritable posse of law enforcement that descended on his car with a variety of allegations. Take a look.

Sean Chaperone:

Got a officer right here over here. Can I get your name and badge number? Are you going to be officer right here too?

Speaker 4:

Oh, the reason why I pulled you over, because I’m the one that actually pulled you over, is a high rate of speed.

Sean Chaperone:

Okay, well, I was cut off. Did you get my speed?

Speaker 4:

What I saw was a high rate of speed.

Sean Chaperone:

So this is-

Speaker 4:

I’m worried about people walking down the street.

Sean Chaperone:

Right. And I’m worried about someone cutting me off.

Speaker 4:

Okay. My issue is people walking down the street. I get it. At that point you should have called 911. “Hey, this is my issue.” We could have solved it then. But you speeding down the street, that’s-

Sean Chaperone:

Doing 35 in a 35?

Speaker 4:

Nu-uh.

Sean Chaperone:

Yes, ma’am. Absolutely.

Speaker 4:

Okay, so the reason why I pulled you over was a high rate of speed. We’re not going to play this game, okay?

Sean Chaperone:

Yeah. No, we’re not. We’re just going to go to court.

Taya Graham:

But even though Sean was now confronted by a full interrogation by these traffic enforcement vigilantes, he had an ace in the hole, so to speak. Because unbeknownst to the cadre of cops, Sean had a dash cam, which was running at the time of the near collision. And when he lets the cops know this, I think it’s curious how they respond to the fact that there is evidence that might challenge their capricious interpretation of the law. Take a look.

Sean Chaperone:

I ain’t got a problem with it. I got a dash cam. Y’all want to say that I’m speeding? Go for it. But the dash cam’s going to make y’all look really funny.

I mean, if she’s going to shine her light in my eyes, I can do the same back.

Speaker 4:

[inaudible 00:05:47], you mind coming up here please?

Sean Chaperone:

I’m going to need a supervisor. Can y’all give me a supervisor?

Speaker 4:

No problem. He just rolled up on here.

Sean Chaperone:

All right, perfect. Hey-

Corporal Williams:

How you doing, sir? Corporal Williams, Stuttgart Police Department.

Sean Chaperone:

All right.

Corporal Williams:

What’s going on, man?

Sean Chaperone:

Not much, [inaudible 00:06:01]. You don’t have to roll it all the way down. How’s it going?

Corporal Williams:

Pretty good. What’s going on?

Sean Chaperone:

Oh, not much. I had someone cut me off back there. They were on a traffic stop. They decided to pull me over. The guy that was behind me was the one that initially cut me off. They told me that they couldn’t catch him, that they decided to pull me over even though he was behind me.

Corporal Williams:

Okay. If he cut you off, how was he behind you?

Sean Chaperone:

Because I jumped around in front of him.

Corporal Williams:

All right.

Sean Chaperone:

He was doing about 25, getting ready to turn. I pulled back over in front of, got in the left-hand lane, passed him, got back over in the right-hand lane, took the right right back here at the stoplight.

Corporal Williams:

Okay. Well, according to the other officer, he said all he saw was you slam on your brakes, stop in the middle of Michigan-

Sean Chaperone:

I did. I slammed on my brakes because I had just gotten cut off and I slammed on the horn. That’s absolutely what I did.

Corporal Williams:

Okay.

Sean Chaperone:

He’s got that part right.

Corporal Williams:

All right. And the car cut you off?

Sean Chaperone:

That is correct. 110%.

Speaker 4:

Well the horn part-

Sean Chaperone:

Can you ask her to get her light out of my eyes, please?

Speaker 4:

[inaudible 00:07:02]-

Corporal Williams:

What’s that?

Sean Chaperone:

Can you ask her to get her light out of my eyes?

Corporal Williams:

Well, if he didn’t see what took place is what I’m saying. You understand that? If he didn’t see the car cut you off because he was on a traffic stop, obviously he’s paying attention to this traffic stop.

Taya Graham:

As I watch this video, I’m reminded of an idea that I think we sometimes forget: the notion that enforcing the law is often subjective and therefore arbitrary. But despite that truism, what happened to Sean here is a stark reminder that once the law is aimed at you, the subjective aspect of law enforcement is simply forgotten. Instead, we, and Sean, are subject to its exacting consequences, often solely because an officer, in their opinion, deem you guilty. And this exacting judgment persists even if the evidence presented challenges their assumptions. Just watch this idea play out as officers give Sean a ticket while simply ignoring his version of events.

Sean Chaperone:

Hey, it’s been well more than 15 minutes. Are we going to go or what? Are we being detained? We free to go? It’s been more than 15 minutes. Turned into an unlawful detainment three and a half minutes ago. We’ve been here 20 minutes, man.

Speaker 3:

Okay.

Sean Chaperone:

All right.

Speaker 3:

Go ahead and roll your window down for me.

Sean Chaperone:

It’s cracked. I can hear you just fine.

Speaker 3:

Okay. That’s cool. I need you to roll the window down.

Sean Chaperone:

I mean-

Speaker 3:

Roll the window open.

Sean Chaperone:

No, sir. I’m not going to. That is against my constitutional rights. I do not have to.

Speaker 3:

Okay. First of all, you need to learn your constitutional rights.

Sean Chaperone:

I do know my constitutional rights. Do…

Speaker 3:

So roll the window down.

Sean Chaperone:

… you know that your vehicle’s an extension of your house?

Speaker 3:

Yeah. Okay.

Sean Chaperone:

Okay.

Speaker 3:

So roll the window down so you can sign this citation.

Sean Chaperone:

I’ll sign the citation. All you got to do is just hand it to me right here.

Speaker 3:

No, I don’t hand my clipboard through the window. Roll your window down.

Sean Chaperone:

If you won’t hand it through your window, then how is rolling my window down going to help?

Speaker 3:

You’re going to lean toward me, you’re going to sign this citation, and we’re going to go about [inaudible 00:08:57], or-

Sean Chaperone:

I can step out and we can sign it. I can step out and we can sign it.

Speaker 3:

Or I’m going to take you to jail for obstruction. You understand?

Sean Chaperone:

Obstruction is a physical crime. You do realize that?

Speaker 3:

You are obstructing my justice.

Sean Chaperone:

Obstructing is a physical crime.

Corporal Williams:

You can go ahead. [inaudible 00:09:15] refused to sign, hand him his copy, and go [inaudible 00:09:17]. It doesn’t change it either way.

Speaker 3:

Are you going to sign my ticket?

Sean Chaperone:

I mean, did he just said… What did he just say?

Speaker 3:

[inaudible 00:09:27].

Sean Chaperone:

That’s why we have to have y’all’s supervisors here to keep y’all honest.

Taya Graham:

Now, the ticket was just the beginning of Sean’s ordeal, a series of events that have forced him to fight back in a way we will be discussing with him soon. But first, I’m joined by my reporting partner, Steven Janis, who’s been looking into the case. Steven, thank you so much for joining us.

Steven Janis:

Taya, thanks having me. I appreciate it.

Taya Graham:

So Steven, you’ve been reaching out to the Stuttgart Police. What are they saying?

Steven Janis:

Well, Taya, not a lot right now. I reached out to the Chief of Police of Stuttgart through his departmental email, asked him a couple questions, most notably, why the obstruction of justice charges? I thought that was kind of weird. I asked him if he actually thought that was a legitimate use of that charge in that situation. I also asked him why they didn’t take into account Mr. Chaperone’s version of events, why they didn’t look for the other driver. I’m waiting to hear back. If I hear something, I’ll mention it in the chat. I haven’t heard it back yet, but I will keep reporting on it.

Taya Graham:

Often when reporting on these types of questionable tickets, there are some underlying reasons rather than just public safety. You’ve been looking into the town itself. What have you learned?

Steven Janis:

Well, it’s really weird. I went to the Stuttgart town website to look through their financial information, budgets, et cetera. Nothing was posted. It was completely blank. I’m showing you on the screen right now. They do not share budget information with the public, which I think raises a lot of questions. They’ve also given police officers a raise, although they weren’t making a lot of money, like $11 an hour for a rookie, so maybe they need to raise money and write a lot of tickets. I get that feeling because they really don’t share information. Lack of transparency always leaves questions unanswered.

Taya Graham:

So I talked about the idea of an arbitrary nature of police power and how it can infect the process of law enforcement. I know you have some ideas on the topic. Can you talk about them?

Steven Janis:

Yeah, Taya. There’s nothing more anti-democratic than arbitrary power, especially police power, because the consequences of when it is imposed upon us are life altering. So, really, giving someone the ability to, say, write you a ticket when it’s not justified, or put you in a cage when there’s no real basis for criminal charges, all results in the same thing, a sort of roving sort of mobile fascism that really can entrap you in a system that’s unjust. And I think that’s why we have to keep our eye on, and always hold in check, indiscriminate and, what we say, arbitrary police power.

Taya Graham:

And now to discuss this confrontation with Stuttgart Police, why he challenged the officers, and how he’s fighting back against the ticket, I’m joined by Sean Chaperone. Sean, thank you for joining me.

Sean Chaperone:

Thank you for having me.

Taya Graham:

So first, tell me why you were pulled over. What are we seeing at the beginning of this video?

Sean Chaperone:

So initially, I had turned left onto the street that I was on. There was a vehicle that had cut me off and had their right turn signal on. After they cut me off, they turned their turn signal on signaling that they were going to turn into the motel. Well, when they had cut me off, I was doing approximately 35. They were doing about 20. They cut me off, I slammed on my brakes, slammed on the horn, and then got in the left-hand lane, went around them, and then got back in the right-hand lane. They never ended up turning into the motel and ended up coming up behind me. Well, I took a right at the stoplight, and that’s when the police got behind me and pulled me over and said that I was going at a high rate of speed.

Taya Graham:

I think it’s interesting that the officer said that he chose to stop you as opposed to the more reckless driver. How did they explain that?

Sean Chaperone:

Yeah, well, initially in that video, he says that he saw both vehicles. He saw me and the vehicle that had cut me off. And then in the video three times, he denies ever seeing the vehicle cut me off. So my question is, what did the officer really see? I think he just heard some things. He just heard me slamming on my brakes and blowing on my horn, and then decided that I was the aggressor even though I was driving defensively.

Taya Graham:

Sean, some people might say you were confrontational, and others might say you were standing on your rights. How did the cop respond to your pushback?

Sean Chaperone:

He initially walked up to the vehicle with an attitude, yelling at me. Personally, I mean, I was just acting defensively. Yet again, I was driving defensively, and then when he comes up acting aggressively, now I’m acting defensively. And I’ve seen people say that, “Well, this is a bad time for an audit.” Well, first of all, this wasn’t an audit. I’m just on my way home. So this is… Exactly, this is just me standing up for my rights. And unfortunately, he got a little upset about it.

Taya Graham:

You seem very knowledgeable about your rights and the rules surrounding traffic enforcement. How do you think that helped you in the situation? How do you think things would’ve turned out if you hadn’t?

Sean Chaperone:

Oh, it definitely helped me in the situation. I mean, towards the end of it, they’re threatening to arrest me. So, I mean, definitely know your rights and record the police. Even if you don’t know your rights, just record the police to hold them accountable because there’s so many times that their body cams come up missing when it comes to court, and the only thing that you have to stand on is your evidence.

Taya Graham:

How did you become so knowledgeable about your rights? What inspired you to learn so much?

Sean Chaperone:

Well, my father’s a retired police officer. He is a retired K9 officer, so that definitely helped. As well as him being a police officer, he has also gone over the last probably four or five years and really hammered to me, educating me on my rights, because he sees it as well. He sees the officers that are stripping people of their rights and he never was that way, but he sees it happening now and he sees that if we don’t stand up for it, we’re going to lose it.

Taya Graham:

Did you have any concern that the officer might violate your rights because of your pushback, because of the way you asserted yourself?

Sean Chaperone:

Absolutely not. If they’re going to violate my rights, if they want to arrest me, I guess that they have every right to do so. I’m not going to let them intimidate me or try and bully me in any way, shape, fashion, or form. Let’s say they would’ve arrested me. I mean, we’d be going to court right now on a counter suit for unlawful arrest. So, no. I mean, for me, personally, it doesn’t intimidate me.

Taya Graham:

So I noticed that you were counting down the time, that the officer only had 15 minutes to write you a ticket. What was your next move if he took over 15 minutes?

Sean Chaperone:

I mean, I wasn’t going to run. That’s for sure. It’s a state specific law. It’s Arkansas Criminal 3.1 that states that an officer only has 15 minutes to write you a citation. So it’s a very state specific thing. I wasn’t going to leave, but I was definitely going to get out of my vehicle, start asking questions, because now it’s starting to turn into an unlawful detainment. So that’s pretty much what I would’ve done.

Taya Graham:

So what exactly was the ticket for?

Sean Chaperone:

So the ticket ended up being for… I think it was reckless and prohibited driving. It’s $150 ticket and currently we are going to court. The court date is, I believe, August 3rd. So it’s going to trial and I will be representing myself and I look forward to seeing the officers on the stand.

Taya Graham:

Now, I think it’s important to expound a little bit on the idea Steven and I discussed, namely the arbitrary nature of police power. It’s important because I think it acknowledges that policing is just as much an idea as it is an institution, and for that reason, something worth examining beyond the usual critiques that views cops and badges as the inevitable result of our ongoing experiment with self-governance.

Let’s remember, as we’ve said before, modern policing was one of the last iterations of democratic governance to emerge, an institution that didn’t evolve until the form resembles today until the mid 19th century. Which is why we need to sometimes examine it in a way that doesn’t simply assume it should, or even inevitably, exist. Not so much to say we don’t need police, but rather a way to truly understand what the prevalence of policing in our country truly engenders. In other words, how does the existence and growth and proliferation of law enforcement actually affect the way we live? To answer that question, as I already mentioned, we need to explore the notion of the arbitrary nature of police power, meaning how the latitude to enforce the law, take our freedom, and sometimes even our lives, affects how we both move through the world and even view ourselves.

First, we need to focus on the idea of what it means to be subject to arbitrary power and how it affects us. I want to examine this idea through the prism of another refrain we hear over and over again from politicians and other elites. Namely, “No one is above the law.” Now, this idea has become an oft used talking point of the mainstream media and their elite group of proselytizing pundits. The concept that the law is an unbiased arbiter that applies to everyone is pretty much a mantra for elites to pat themselves on the back as objective arbiters of justice.

Well, fair enough. But it’s an intriguing invocation when you consider just how the law works, especially if you view it through the lens of the stories we have reported on for this show. Because as we’ve seen, in case after case, how the law is applied can be quite arbitrary. In other words, whether we’re talking about a Texas firefighter falsely accused of a DUI, a man whose car was searched while he was walking his dog, or this story about a quite subjective rendering of traffic laws, all of this means, in reality, is that the law is arbitrary for those of us who actually have to live with it. Which, of course, sits in stark contrast to those who don’t, namely the cops who enforce it. How do I know?

Well, consider the predicament of a dedicated New York City traffic cop, Matthew Bianchi. Bianchi was a veteran officer who actually liked enforcing traffic laws. That’s because, at a young age, Bianchi lost a friend in an accident to a reckless driver. Therefore, when he felt someone was being particularly over the top and driving poorly, he would write a ticket as the law requires. That is with one fairly broad exception. Turns out New York cops are given what are known as courtesy cards. What are courtesy cards? Well, basically a get out of jail free pass handed out by police unions, so officers can give them to friends, family, and anyone else they want to. So when an officer pulls someone over, regardless of the infraction, the informal rule is to let them go, provided they have a courtesy card.

Unfortunately, for Bianchi, this was a problem. He found himself often having to let people go who were endangering others. To prove his point, he cited an encounter when he pulled over a driver who was not just recklessly speeding but didn’t even have a license or insurance. That same motorist had a courtesy card, which he refused to honor and subsequently ticketed the driver. But this exercise of officer discretion did not go unnoticed. Soon he found himself the recipient of retaliation across the department. He was demoted and the union told him it would not protect him. He was sent to work in the borough of Staten Island, where he estimated half, that’s 50% of the people he pulled over, had courtesy cards.

To make matters worse, officers can buy them for a dollar a piece from the union, no word on who keeps the dollar by the way, and hand them out to anyone they want. Things came to a head when Bianchi refused to honor a card from a relative of the department’s highest ranking officer, a move that led to further demotion. Now, Bianchi is suing over what he says is unfair retaliation and abuse of his discretion. But I think this whole ordeal makes a more interesting and important point. And that is, of course some people are above the law. In fact, the people who are empowered to enforce it are not just above it, but can grant impunity to friends, family, and anyone else they please. And this so-called unqualified immunity is applied indiscriminately to anyone and everyone who happens to know a cop who happens to have a dollar.

But it also points out the impact arbitrary enforcement has on a democratic, supposedly free society. Because if the people who enforce the law are not subject to it, then the law itself truly has no meaning. If the cops who profess to be the bastion between uncivilized and civilized society can dole out pardons like confectionary treats, then what we have is not a nation of laws, but a Congress of tyranny. That’s right. I said it. I know it sounds a little discomfiting, but it’s true. And please let me explain why I used it.

Let me start with a question. Have you ever worked for a bad boss who made your life miserable? Who constantly changed your assignments, ignored your input, belittled you in front of others, called you at all hours and otherwise just treated you like a toy? Because if you have, then you know what it’s like to work for a tyrant. Someone who’s bounded by no rules, a person who implicitly works under the assumption that what applies to you does not apply to them. And by embracing that notion, they are then free to wreak havoc on your life any way they see fit. Well, that’s called tyranny, and I think you can see how this concept is applicable to the police. Because if cops in New York can enforce laws on others that don’t apply to themselves and their friends, then they’re basically above the law. And if they can retaliate against people who follow the law honorably, they can assure they are immune from it. That means they, in a sense, become the law itself, which literally allows them to engage in a form of individual tyranny towards the people they subject to it.

Think about it. How can the institution that professes to fairly enforce the law simply exclude themselves from it? How can a group of people called law enforcers use that same power to evade it? The point is that this idea of occupational immunization simply makes the law wholly subjective. That is, when the law enforcers can also be the lawbreakers, the whole process becomes subject to the whims of an individual, namely a tyrant. That is why we have to continue to hold cops accountable, because clearly it’s up to us, the people, to guard our freedoms and preserve our rights from the people who would otherwise abuse them.

I want to thank Sean for coming forward and helping educate us about our rights and sharing his experience. Thank you, Sean. And of course, I have to thank intrepid reporter, Steven Janis, for his writing, research and editing on this piece. Thank you, Steven.

Steven Janis:

Taya, thanks for having me. I really appreciate it.

Taya Graham:

And I want to thank friends of the show, Nolie D and Lacey R, for their support. We appreciate you. And a very special thanks to our Patreons. We appreciate you, and I look forward to thanking each and every one of you personally in our next live stream, especially Patreon associate producers, John E.R., David K., and Louis P., and Super Friends, Shane Busta, Pineapple Girl, Chris R., Matter of Rights, and Angela True.

And I want you watching to know that if you have video evidence of police misconduct or brutality, please share it with us and we might be able to investigate for you. Please reach out to us. You can email us tips privately at par@therealnews.com and share your evidence of police misconduct. You can also message us at Police Accountability Report on Facebook or Instagram, or @EyesonPolice on Twitter. And of course, you can always message me directly @TayasBaltimore on Twitter and Facebook. And please like and comment. You know I read your comments and appreciate them. And we do have a Patreon link pinned in the comments below for Accountability Reports. So if you feel inspired to donate, please do. We don’t run ads or take corporate dollars, so anything you can spare is truly appreciated. My name is Taya Graham and I am your host of the Police Accountability Report. Please, be safe out there.