Editor’s note: After this episode was recorded, Authentic Brands Group announced that Sports Illustrated would live on after Israel’s Minute Media acquired publishing rights for the magazine.

Layoffs, lawsuits, license revocations. The tragicomic spectacle unraveling at Sports Illustrated bears all the signs of a familiar tale: how hedge funds can take a functional, beloved brand and transform it into an anemic husk of its former self by mercilessly draining it for profit. Washington Post National Sports Culture and Politics Reporter Michael Lee joins Edge of Sports for a frank talk on the putrid effects of venture capital and hedge funds on sports media, Black Lives Matter in sports, and more.

Studio Production: David Hebden

Post-Production: Taylor Hebden

Audio Post-Production: David Hebden

Opening Sequence: Cameron Granadino

Music by: Eze Jackson & Carlos Guillen

Transcript

The following is a rushed transcript and may contain errors. A proofread version will be made available as soon as possible.

Dave Zirin:

Welcome to Edge of Sports TV only on The Real News Network. I’m Dave Zirin.

We are going to talk right now to Washington Post national sports culture and politics reporter Michael Lee about sports journalism, Black Lives Matter in sports, activism, and what it all means. Let’s talk to him right now, Michael Lee.

Michael Lee, thank you so much for joining us here on Edge of Sports TV.

Michael Lee:

Hey, thanks for having me.

Dave Zirin:

All right, let’s put on our serious hats, if we can. It looks like the NFL might be buying a stake of ESPN. We know what’s happening with Sports Illustrated, which makes a lot of people around our age well up a little bit. The Athletic, where I know you used to work has taken over the New York Times sports page. Beyond the work of folks like yourself, is the era of a thriving independent sports media as we have known it, is it done? Are we past the point of having the kind of sports media that I think we so dearly need?

Michael Lee:

As long as the money is shifting towards hedge fund guys and venture capitalists, yeah, that’s what’s happening. I think when you don’t have creatives in charge and having the vision of creatives, then all you’re going to do is just try to make a money-making operation that is doomed to fail. Primarily because for these creative industries, like journalism is…

I mean, yes, we have a serious task of holding truth to power and trying to make sure that we uphold certain values and principles. We’re protected by the First Amendment and everything like that. But when people who are running it view it as leverage to make money as opposed to a means to serve a greater purpose to the people, you’re going to see the collapse, you’re going to see things fall, you’re going to see things ruined, mainly because you don’t have the vision.

And that’s really what I look at whenever I see these things happen, where we have layoffs, we have buyouts, you have cuts, you lose talent. And you don’t just lose talent, but you lose your soul because a lot of times, the people who get cut are the veterans who’ve been there for years. They understand the systems. They understand the angles. They know all the anything.

If you have a veteran basketball player, a football player, they can teach the young guys how to manipulate things and operate and maneuver more effectively. But if you cut those people out, you’re doing damage for the people who are coming up in their development.

So I think that, yeah, as long as the people with money don’t have that vision and their whole purpose is to try to view this as a means to make money as opposed to a greater purpose in terms of educating people, informing people, and also just providing them an outlet for pleasure, you’re going to see situations like this only get worse.

And I think that’s where we are now, because the money, and where the money is being shifted, the big money, the billionaires, when they start coming in and manipulating this and not seeing the vision from an artistic perspective, that’s where you see the failings.

Dave Zirin:

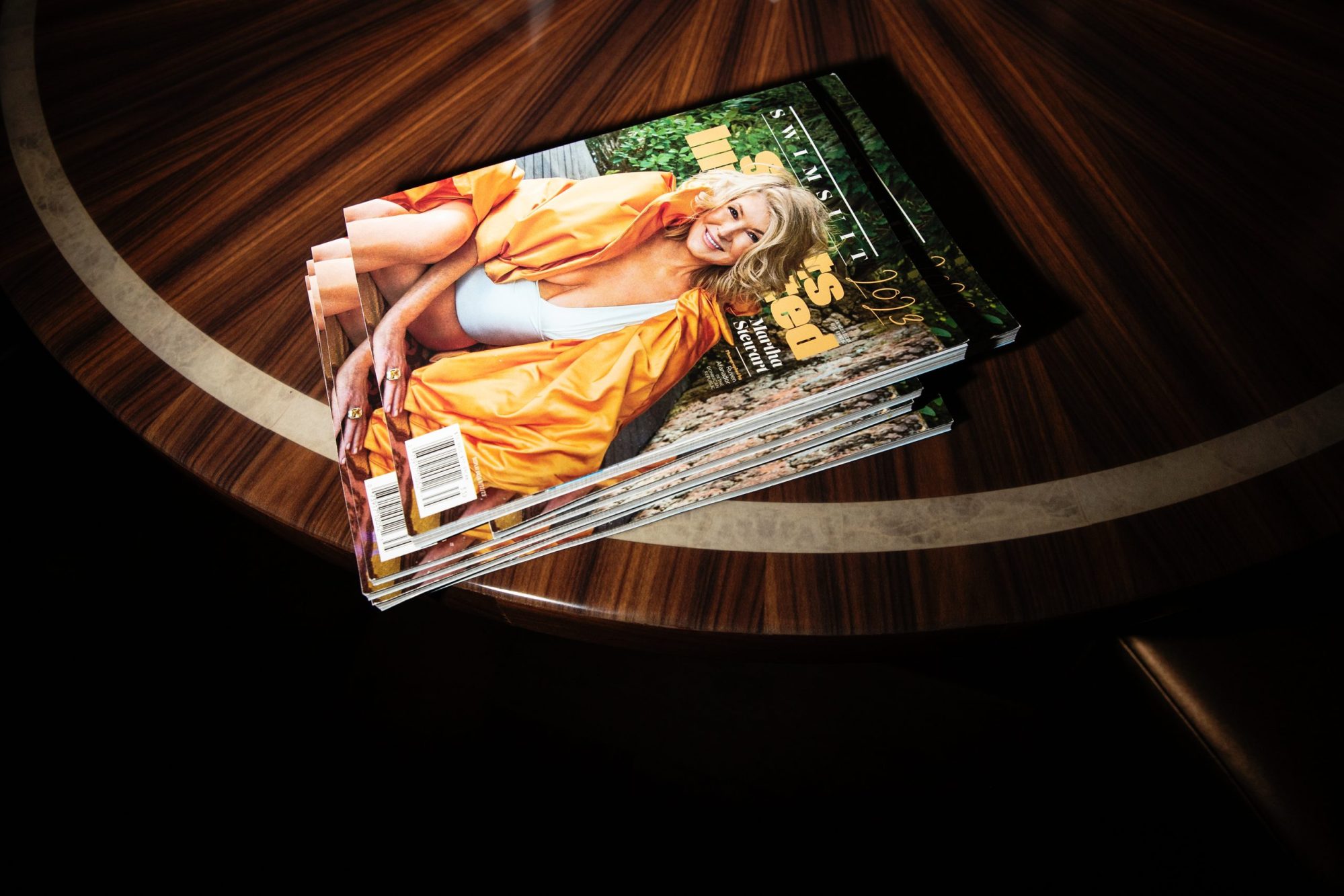

Wow. I realize I spoke for you in my question, talking about Sports Illustrated. I know when I heard about what is basically its downfall, it moved me, thinking about what it meant to me coming up. But I don’t know if it had that same effect on you as a young person looking at that magazine and thinking, this is what I want to do. I was wondering if you could reflect on that for a moment.

Michael Lee:

Absolutely. I mean, Sports Illustrated was the ideal. It was the model. So many great writers came through there. I know the inspiration for me to even get into sports journalism was Ralph Wiley. That was the guy that I just looked up to. One of the first books I read on my own outside of school, guys like him, Rick Reilly. There’s so many. Steve Rushin. So many great talented guys — I could go on all day. Jack McCallum. People who I read constantly and tried to take in what they did and try to create my own style based off of what I read.

It was a model magazine. I would get copies every week, and I would devour it, and not just because I love sports, but because I love writing, and that’s what inspired me. So I don’t know where kids are going to find that inspiration the way I did.

Obviously things have changed. You don’t have a physical paper or a physical magazine the way you did. You just scroll on your phone or whatever, on your computer, so it’s a different feel. But it’s something about, for me, going out to the mailbox, having something that was addressed to me, and feeling those pages and flipping those pages and reading that, and it was a great feeling.

My kids, I don’t know where they’re going to get that kind of rush. Because it’s the same kind of rush I would get from music when I would have a CD or an album or something physical in my hand that really made it seem like a dream.

Dave Zirin:

Well, just like you and I would read Ralph Wiley’s articles and see his name and think, ooh, that’s who I want to be.

Michael Lee:

Yeah.

Dave Zirin:

There’s no doubt in my mind that people read your work and see the name Michael Lee and say, ooh, that’s who I want to be.

Michael Lee:

Yes. I got a little extra money for you.

Dave Zirin:

But there’s a big but though. There’s big but — No, no, no. There’s a big but here. Don’t worry. What is your advice then to aspiring sports journalists? Is this still a profession worth pursuing? If a young, bright-eyed, bushy-tailed person with talent came up to you and said, I want to be like Michael Lee, what do you say to them?

Michael Lee:

Well, what do you want to be when you say you want to be like me or anybody else in this profession? Do you want to be somebody who does what he loves, or do you want to be somebody who wants to be famous? Do you want to be a celebrity in this, or do you want to be somebody who’s really trying to seek the truth or try to find inspiration and really try to pursue your passion?

If you’re going to pursue your passion and you pursue what you love, everything else is going to fall into place. You’re going to face disappointment. You’re going to face cuts. You’re going to see a lot of your friends and colleagues get dismissed, and it’s going to be disheartening. But what is motivating you, and what is it that you really want out of this business?

If you just think you’re going to go in there and just be on ESPN and become a Stephen A. Smith and just have a top-ranked show and make millions of dollars, that’s going to be hard. There’s only one guy that’s doing it right now like that.

But if there’s something in it that you want out of this, if there’s something that you dream about doing. Like me, I knew my ceiling as a basketball player was high school. I wasn’t going to go beyond that. But I also knew I wanted to be around basketball one day. Then I wound up covering the NBA for 20 years, and covering three Olympics, and the multiple 13, 14 NBA finals, and however many All-Star games.

And so I got a chance to be around basketball because it’s what I wanted to be around and what I love. And so if you feel like this is what you want to pursue, then don’t let anybody… Don’t let the nos keep you from pursuing your dream because you’re going to get a lot of nos. I tell this when I talk to college kids sometimes, the difficult thing in life is when you realize that nobody cares, really, about your feelings, and not everybody’s going to like you.

And so when you get those things through your skull, what do you have left that you’re going to be willing to pursue and fight for? And if it’s yourself and if it’s your passion, then you’re going to find that worthwhile. It’s going to be a struggle, but everything’s a struggle. You’re not going to be able to walk right in and have your dream job right away.

I remember covering high schools out of college and being frustrate, and wondering if I was ever going to get a breakthrough. But I look back and I appreciate those times. I appreciate that struggle because it made me more appreciative of when I actually was able to have those moments where I’m like, man, I can’t believe I’m doing what I always dreamed of doing.

Dave Zirin:

Recently, a writer that we both know, Jeff Pearlman, was asked that question. You might’ve seen this on social media, and he gave a response that, I do have to say, felt like a response that was about five years old, where he said, be a Swiss army knife, become an expert on everything, and you’ll have no problem.

And a lot of people pushed back and said what you said, frankly, which is these VCs are tearing these jobs apart. What does it matter if I can podcast, if I can write, if I can do TV? What does it matter if, at the end of the day, like you said, Michael, the people with the most institutional knowledge are usually the first people on the chopping block?

I know this industry is in such flux, so it’s impossible to ask you to have a crystal ball or anything. But do you see, in the future, a way around this, so people like you and I can tell young sports writers that this is a life worth living as long as you’re not obsessed with that end goal but love the process?

Michael Lee:

Yeah, I think a lot was lost in what Jeff was trying to say. I think he meant it in the most sincere, thoughtful way possible: make yourself indispensable. The one thing about, like I said earlier, is that no one’s really indispensable, and everybody’s replaceable, and we just have a chance to occupy positions for as long as somebody’s willing to employ us. And you have to view that through the level of everybody.

Think about what we had just this past month. We had Bill Belichick, who people say is the greatest coach of all time, retire, and he was replaced a day later. They found his replacement a day later. It didn’t take a long to find somebody to fill those shoes. Nick Saban, the greatest college coach of all time, said, I’m leaving college football. They found his replacement within a day or two.

So no matter how great you are, no matter what you do, you can always be replaced. They’ll always find somebody that’s willing to do your job. So what you have to do is really value the opportunities that you get and take advantage of it because they’ll always find somebody who’s willing to do what you do. They may find one person who’s willing to do three or four jobs that people have been doing. And that’s just the way it is.

And so you got to understand your position. If somebody is writing a check and you’re salaried and you’re an employee, then you have to understand that you can easily be let go no matter what you’ve done or what your accomplishments are, no matter what your achievements are. They allow you to maintain that seat for a little bit longer. But just know that you can’t ever get complacent. You can’t ever sit back and think, well, I’ve made it.

One of the greatest things, books, Jackie Robinson, he always said, “I never had it made.”

Dave Zirin:

That’s right.

Michael Lee:

And you could look at him and you could say, oh, what you did. You are a rookie of the year. You won World Series champion. You did all these great things. You broke the color barrier in baseball. But you can’t ever get to a place where you feel like, well, yeah, man, I’m finally here, and it’s just great. You got to know that you can always be replaced. You’re always expandable, so you got to take it and appreciate it.

When I first started covering the NBA, it wasn’t a job that I was handed. I was filling in for somebody. And I’m not a big Eminem fan, so I’m not going to act like I am, but I played “Lose Yourself” like every day because I was really in that moment and I knew I couldn’t let it go. This is my shot. I had to go in there, and I had to have this desire to like, okay, they opened the door for me, but they messed up, because I’m coming in, and I’m ready to… I’m busting through the door. You’re not going to kick me back out now.

And that’s the mentality that you have to have. You’re going to face disappointment. I faced disappointments throughout my entire career. And so there are just things you got to understand and you got to value. And you can’t really sit back and say, oh, man, it’s so tough, man. I don’t know if I can really fight through it.

It is hard. It’s disappointing. And I’m speaking as somebody who’s really faced some hard times. But you got to also know that, when you get those opportunities and you have the chance to do something great, that you got to take advantage of it and know that it’s fleeting, just know that it’s fleeting, it’s not promised. Nothing is promised to you in this business as long as you’re relying on someone else to pay your salary.

Dave Zirin:

Right. One more journalist question, if I could. You did an amazing job on, let’s call it the beat, of the Black Lives Matter movement in the world of sports. And sometimes I take a step back and I think, wow, Colin Kaepernick taking that knee for the first time was seven-and-a-half years ago.

Michael Lee:

Amazing.

Dave Zirin:

Amazing. Seven and a half years. That’s like the difference between 1960 and 1968. It can be a political lifetime. So that issue of athletes using sports as a platform to speak about racial inequity and police violence, has that era, is there a cap now on that era and it needs to be rebuilt? Or you have a mind of, well, it’s ongoing. It’s just more of a placid period right now?

Because I know a lot of people who think, yeah, kids 18 right now were 10 when Kaep was doing his thing, something’s going to have to be rebuilt because that era has been effectively, I don’t want to say memory holed, but effectively put in the backseat. And I wanted to know your perspective.

And then with the bigger question, when do you know when a story is over?

Michael Lee:

Man, that’s a great question, because I’ve actually thought about that myself. I’ve wondered where is the activism in professional sports, and was that a moment that we just had, and we just got to just appreciate that we had it? Because I honestly don’t have the answer. And it is something that is floating through my mind.

One thing that, when I think about what Kaepernick did, it was such a risk, and he lost his career. And you can even see up until last fall, he still wanted a shot back in the NFL that you knew was never going to happen.

And I think that all you’ve seen since has been a lot of safe protests. There are moments where the NBA has allowed players to take a knee or they’ve allowed guys to put things on the back of their jersey during COVID. And I think that guys are finding safe spaces to say things that aren’t offensive that don’t really put them in a position where they can lose anything because there’s so much to gain.

There’s so much money to be made now. The salaries have reached exponential levels that we probably didn’t think could happen. Ohtani got a $700 million deal. If you can reach that kind of money playing a sport, you might want to zip it up a little bit because they will get rid of you if you make everybody feel a little bit too uncomfortable.

So I think that the money has silenced guys. And also knowing that what you can lose, guys are trying to figure out ways that they can maneuver without losing anything. And I think that’s where we are now.

And there’s not issues that are really pushing them to speak out. Maybe there are, but I noticed that no one’s saying anything about any of these wars going on in the world. No one’s speaking out on anything on that behalf because there’s so much more to lose than there is to gain. And I think right now guys are just trying to get this money.

Dave Zirin:

Yeah. It’s funny, I was talking earlier with former NBA player Tariq Abdul-Wahad, and he said something very similar as he’s attempting to find athletes to speak out for a ceasefire with regards to Israel and Gaza. So what you’re saying rings very true.

Michael Lee:

Yeah, I think you’ve seen guys… You saw what happened to Kaepernick, he lost it all. And I don’t want to go to this extreme, but think about it like this. I know sometimes people say, why are there no more MLKs? Why are there no more Malcolm Xs? Why are there no more leaders of that caliber? Well, they were killed. And everyone saw what happened to them. So if that’s the case, if that’s the reward at the end, not everybody’s brave enough to say, I want to take that path.

Just to bring it to the sports level, Kaepernick spoke out, and what he did was noble and admirable and everyone respected it. And obviously, he got respect for days for what he did, but he lost what most of the guys aren’t willing to sacrifice, which is their careers.

And when you see him even saying, I want to play now, and I’m still capable of playing if you give me a chance, and everyone’s turning their head to him, it’s like, well, dang. What do I really want out of this life? Do I want to be an activist or do I want to be an athlete?

And I think that if you’ve invested your whole life in being an athlete, and you’ve kind of gone down that path, and this is what you’ve made your whole life about, you’re not willing to give that up. And if you want to really try to do things when you’re done playing, maybe you will. But there’s so much at stake beyond just the money, but also your career, that I don’t think guys are willing to lose all that the way Kaepernick did.

Dave Zirin:

And of course, got to mention that you’re wearing a Muhammad Ali sweatshirt right now.

Michael Lee:

Yes, yes, yes.

Dave Zirin:

And it’s one of those things where it’s been said by others that he was only truly embraced by this country once he lost the power of speech.

Michael Lee:

Absolutely.

Dave Zirin:

And this idea that they make you make that choice between being an athlete and an activist, when I think a lot of folks would have no problem, if they felt like the risk wasn’t there, of wearing both hats with comfort and confidence.

Look, we’ve been talking about journalism in big picture, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t bring up, before you go, a work of journalism that you did recently in December that was so good. And I have spread this around all over the place.

You went to Mississippi, and you asked a very provocative question: If youth football is going down all over the country, largely because parents are becoming more educated about injuries and concussions, why is it still so prominent and even growing in Mississippi and Alabama?

But you didn’t just think about it theoretically. You went down there and you spoke to folks to get answers. What did you come up with, and how did it change your own views and ideas about youth football?

Michael Lee:

It was great. It was an altering experience on a lot of fronts, because I think you can just look at it and just say, oh, everyone, they’re in a poverty-stricken area. They’re poor. What else do they have to push them to achieve?

And in Mississippi, that’s probably one of the places where it actually fits. There isn’t a lot to do in Mississippi. There aren’t a lot of things that are going to provide a positive outlet for kids down there. Such a unique place in the country where there aren’t a lot of big towns, there aren’t a lot of big cities, distractions and things to try to pull you away. There’s a country culture there. There’s a toughness there that’s instilled in these kids from a very young age.

And so playing football is just a traditional thing. Your uncles played it, your father played it, everybody played it. So when it comes to be your turn, you got to do it.

And so for me, the one thing that I came away with, though, that really struck me was that while we talk about poverty from a material perspective, what about poverty from a moral perspective? Which one would you value more? Would you want to be in a situation where you have all the money in the world but you’re not loved and supported?

When I went down to Mississippi, I saw communities where people were living in trailers and living in really backwoods conditions, but what they had was the support of their loved ones. What they had was a constant connection to a community and to the people who love them. And so I came away with a sense that, yeah, while they may be lacking in some areas, they’re winning in other areas.

I had a great conversation with one of the coaches for Starkville High, which is a school that I featured in the story. And he was like, there’s a pride in these homes. Even though you may look and say, yeah, these are poor places and they don’t have a lot, but inside that home, there’s a lot of pride. And so the kids that come out of there are going to embody what’s being taught inside that home.

And he said, you can find a house on the highest hill, and you can find the biggest mansion on the highest hill, but I guarantee you, you won’t find more love in that house than you’ll find in these houses here.

And so when you take a step back and try to figure out what’s really important, what’s valuable to you, what do you value, what means the most to you, is it having a paycheck that allows you to buy whatever you want, or is it having the love and support of people who are going to be there for you through whatever?

And some people are fortunate enough to have it all, but not everybody does. But if you value one above the other and you’re getting that fulfillment and that support and that love from the people who you care about, then are you really lacking? And what are you really lacking for?

And so I came away there with just a different perspective on a lot of different things, but one thing that I came away too is that football is something that we definitely knock because of the damage it can do to your head and your body, the long-term ramifications that it can have. But there also are people who are able to use football and not just to try to get to the NFL and become rich, but to get out of situations where they can get a college scholarship and get a job and provide for their families in a way that they may not have been in the past.

So there’s so many ways you can look at it. And so that’s what I came away with this is like, it’s not as simple as saying don’t do it because you might get head trauma, because you might not get head trauma, and you might be able to provide for your family.

Dave Zirin:

Well, you know what? That’s a very interesting perspective for folks to take in as we head into the Super Bowl hype season, for sure.

Michael Lee:

Absolutely, yeah.

Dave Zirin:

To put it mildly.

Hey, Michael Lee, I really appreciate your time. Everybody should just Google “Michael Lee Washington Post” — Make sure you don’t put the word “senator” by mistake because that’s a very…

Michael Lee:

Please don’t do that [laughs]!

Dave Zirin:

…That’s a very different dude. So do “Michael Lee sports Washington Post”, and you’re going to get a treasure trove of articles, the likes of which will restore your faith in sports journalism.

Michael, thank you so much for joining us here on Edge of Sports TV.

Michael Lee:

Hey, thank you, Dave. It’s far too kind, man. I appreciate it, man. I need to take you on the road, man. You’re like Flavor Flav over here, man. ou got me all hyped.

Dave Zirin:

Hey, you know what? If I could be Flavor Flav, that’s a life worth living. That’s all I’ve got to say. Get up, get up, get, get, get down. I’ll do it. I’ll do it. I’ll embarrass myself. But that’s okay. Thanks so much for joining us.

Michael Lee:

Thank you for having me. It was great.