The Big Three have fallen like a house of cards.

The UAW’s historic Stand Up strike has come to an end—for now, at least. After forty-four days on the picket line, the Auto Workers have reached tentative agreements with each of the Big Three automakers. GM was the last domino to fall on Saturday, October 30, just days after Ford and then Stellantis acquiesced to their own tentative deals.

50,000 strikers have returned to work, and all 146,000 Big Three union members are now voting on the contracts. While it’s up to the workers to decide whether the deals are adequate, one thing is already clear: the UAW has turned the tide on decades of concessionary bargaining.

For this episode, we invited Barry Eidlin back on the show to unpack the gains and wider implications of the UAW’s tentative agreements. Barry Eidlin is an associate professor of sociology at McGill University, who studies class, labor, politics and social movements. He is the author of Labor and the Class Idea in the United States and Canada, published by Cambridge University Press in 2018.

We explore why the agreements may represent a shift toward a “new kind of unionism,” how the UAW’s prospects for organizing the rest of the auto industry may have changed, and what listeners should be following in the rest of the labor movement.

Additional links/info:

Read Barry Eidlin’s article on the Belvedere plant in Jacobin.

Support the show at Patreon.com/upsurgepod.

Follow us on Twitter @upsurgepod, Facebook, The Upsurge, and YouTube @upsurgepod.

Hosted by Teddy Ostrow

Edited by Teddy Ostrow

Produced by NYGP & Ruby Walsh, in partnership with In These Times & The Real News

Music by Casey Gallagher

Cover art by Devlin Claro Resetar

TRANSCRIPT

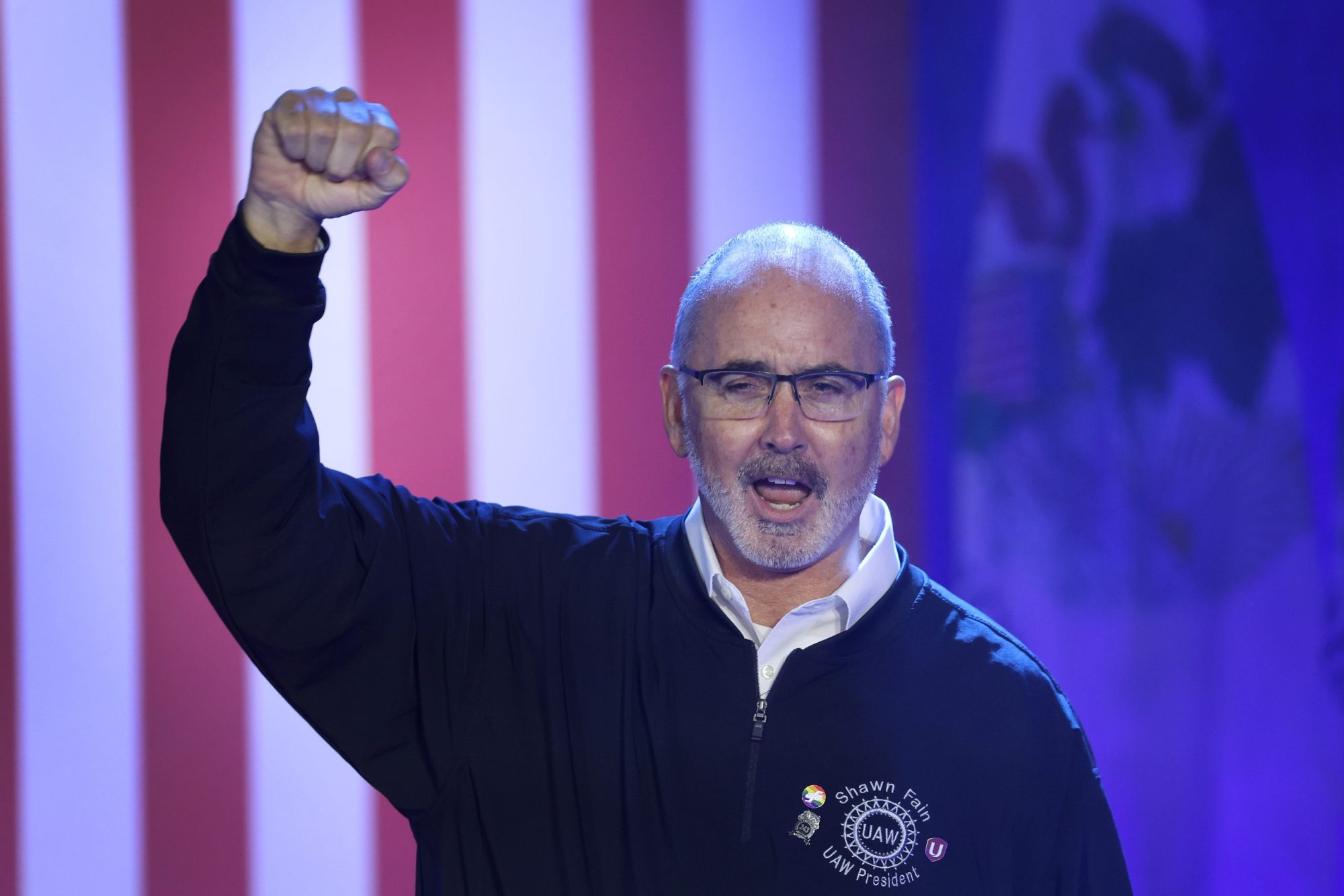

Barry Eidlin: It really speaks to Shawn Fain and the new UAW administration’s commitment to a more class struggle vision of unionism, right? Where that’s really the story of the UAW contract campaign and the Stand-Up-Strike that ensued is one of developing a much more explicit framework of class warfare and that we are fighting not just for auto workers, but for the entire working class, that we are engaged in a class struggle with our billionaire class enemies, drawing these clear dividing lines and mobilizing workers around this broader vision.

Teddy Ostrow: Hello my name is Teddy Ostrow. Welcome to The Upsurge, a podcast about the future of the American labor movement.

This podcast covers the renewed militancy of the United Auto Workers, the legendary union that, for the first time in its history this year, struck each of the Big Three automakers at once. That’s Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis.

The Upsurge is produced in partnership with In These Times and The Real News Network. Both are nonprofit media organizations that cover the labor movement closely. Check them out at inthesetimes.com and therealnews.com where you can also find an archive of all our past episodes.

And quick reminder: This is a listener-supported podcast. So please, if you want it to keep going, head on over to patreon.com/upsurgepod and become a monthly contributor today. You can find a link in the description. We can’t do this without you.

The Big Three have fallen like a house of cards.

As of last weekend, the UAW’s historic Stand-Up-Strike came to an end. After forty-four days on the picket line, the Auto Workers have now reached tentative agreements with each of the Big Three automakers. GM was the last domino to fall on Saturday, October 28, just days after Ford and then Stellantis acquiesced to their own tentative deals.

50,000 strikers have returned to work, and all 146,000 Big 3 union members are voting on the contracts, which are expected to pass. By the time this episode is published, some of them may have already been ratified.

Now, while it’s up to the workers to decide whether the agreements are good enough for them, it’s already pretty clear: the UAW has turned the tides on decades of concessionary bargaining. Indeed, when the union declared that record automaker profits warrant record labor contracts, they were not kidding.

The gains are tremendous. I can’t list all of them in this introduction, and we have an excellent guest to discuss the TAs, but for a taste: we’re talking about double or even triple digit raises across four and a half years; the reinstatement of cost-of-living allowances, or COLA; the abolition of wage tiers across the Big Three; the right to strike over plant closures and other investment decisions; a clear and shortened pathway for temps to be made permanent; and the inclusion of some electric vehicle workers in the union’s master contracts with the Big Three.

Not everything the union had demanded was won. Workers did not win a 32-hour work week, for example. Nor were benefit tiers abolished across the companies, meaning tier two workers will still lack defined benefit pensions and retiree medical benefits. The union has not minced words, however. It’s clear that the intent in future contracts is the gaps once and for all. Given what they’ve achieved in this round, one might be foolish to doubt them.

Beyond the specific contract items, the Stand-Up-Strike has also been just deeply inspiring. For other workers, for union members, and for all working class people, who saw the autoworkers fight and win, with a leadership openly declaring war on corporations, who have been stealing the wealth that we create for as long as we can remember.

There is a lot to unpack about the content of these agreements and their wider implications, so I am thrilled that we got Barry Eidlin back on the show to help us.

Barry Eidlin is an associate professor of sociology at McGill University, who studies class, labor, politics and social movements. The author of Labor and the Class Idea in the United States and Canada, published by Cambridge University Press in 2018, Barry is an expert on the decline of labor unions in North America. But he also has got his finger on the pulse of its potential resurgence.

That’s why I interviewed him on Episode 5 back in April to help contextualize the contract campaign of the UPS Teamsters earlier this year. And it’s why now I thought he would be the perfect guest to unpack what these tentative deals mean for the Big 3 auto workers, the UAW, the wider mostly non-union auto industry, and of course, the broader labor movement.

Now, before we get to the interview I just wanted to inform listeners that after this episode The Upsurge will be taking a short hiatus from our normal schedule. Having produced regular episodes every two or three weeks for nearly a year now, we are going to take a moment to break and develop the next moves for our podcast. We intend to update listeners and especially Patreon supporters in due time.

Alright, on to my interview with Barry Eidlin.

Barry Eidlin. Welcome back to The Upsurge.

Barry Eidlin: Great to be here, Teddy. Thanks for having me back.

Teddy Ostrow: Thank you. There’s a lot to discuss, but first I want to just give you an open ended question—give us your broadest assessment right now of the UAW’s tentative agreements. By the time this posts, it’s possible some of them may have been ratified. What do these deals really mean for the auto workers in 2023?

Barry Eidlin: Yeah, I think, I mean, the first thing to say, obviously, is that these deals are in the members hands now and it’s the decision of the members whether or not to ratify them.

And so I have no position on how members should vote on these contracts because that’s not my call. But compared to what we’ve seen in recent years, this is a major step forward, and union leaders will often talk in terms of transformative victories and what have you. But if you look at what they’ve won here, I think that you can make the case that this is a transformative victory for the United Auto Workers.

And regardless of the vote outcomes, this is an incredibly solid base to build on. They’ve basically made huge steps forward in undoing four decades of concessionary bargaining where they’ve won these contracts that really make some headway in getting rid of tiers. So the multi-tier employment where you have different classifications of workers doing the same job, but getting paid different rates, you have basically the elimination of the perma-temp category, so these workers were classified as temporary, but then work for years. There still are temp workers, but they’re capped at nine months. You have these sizable, across the board wage increases that are much more targeted towards the bottom end of the pay scale.

Then I think we’re going to be talking about it later, but you know, these sort of, not restrictions, but these, interventions in companies investment decisions—so basically sort of expanding the vision of the union. And I think more broadly, what we’ve seen, this is the first time that the UAW ran a contract campaign, and really mobilized members in the lead up to the contract negotiations. So you have a membership that’s just much more engaged now, and, in the event that there’s a sizable no vote, we don’t know how that’s going to turn out, but it will be a result of that mobilization, right?

It’s not that the contract is bad or concessionary, it certainly is not, but it will be because members have been mobilized and their expectations have been raised. And so I think that we’ve really made some serious steps towards transforming what had become a corrupt, moribund union into something that is now, the UAW is now sort of really back out front, as they themselves say, leading the class war.

Teddy Ostrow: I think there are definitely also—we had you on last time to talk about the Teamsters—some pretty similar, but also different echoes about the contract campaign there and the gains that were made. I want to talk about one specific win that you wrote about, one of the biggest wins we saw was at Stellantis. They agreed to reopen and quote unquote, idled, but really closed auto plant in Belvedere, Illinois. This was one of the dozens of plants closed over the past 20 years by the Big 3. And the union also won 5, 000 more jobs at the company, which is remarkable because Stellantis had gone into negotiations planning to actually shed 5, 000 jobs. So this is a really major turnaround and … you did write a great piece in Jacobin Magazine about why this is so important for the workers of Belvedere in their own right, but also more broadly, how this may represent the beginning of some sort of shift, perhaps, in the way the union conceives of its own role in the economy. Can you lay that argument out for us?

Barry Eidlin: Yeah. So I think what we need to consider is that, you know, over the past 75 years, basically since World War II, there’s been this shift in labor’s priorities, and in the UAW, the United Auto Workers in particular, the president in the 1940s through 1970, when he died, was this guy, Walter Reuther.

He assumed the presidency in 1947, but he was the General Motors director in 1945. He certainly had his flaws as a labor leader, but he did not lack in vision, and in sort of having a broader political perspective in his view of what labor’s role was. And he really tried to advance a position where labor was going to play a role, not just in securing better jobs and working conditions for workers, but in actually shaping the economy and the polity, that they would have a key role in doing that. And so in the 1945 negotiations, he had this whole plan that the UAW called Purchasing Power for Prosperity. This was in the aftermath of World War II, where there was massive productivity gains to fight the war, massive inflation, but also, wage restraint, there were price controls too, there was wage and price restraints during the war, and so workers had been worked to death and had been producing like crazy to win the war effort.

And then people were looking to the after war period and were really concerned that they were going to get left behind in the midst of what it was anticipated to be, this huge inflationary surge. And so what Reuther proposed was Purchasing Power for Prosperity, which was a 30% across the board wage hike with no increase in car prices.

So it was basically forcing, trying to force the companies to transfer profits from capital to labor. And this resulted in a 118 day strike against General Motors that won some significant wage increases, but ultimately lost on this Purchasing Power plan. And then as a result, that was the beginning of this sort of like clawback of labor’s momentum.

That was when you saw the Republicans assume a majority in the Congress in 1946, they passed the Taft Hartley Act over President Truman’s veto in 1947. And you get to 1950 negotiations and it’s a much different scenario. So Reuther’s vision is really hemmed in by that point. And so you basically end up with a deal that’s called the Treaty of Detroit, where Reuther was able to get the company to invest heavily in its workforce in the sense of guaranteeing basically widespread job security, pensions, regular wage increases tied to the cost of living, but in exchange gave up that broader vision. They gave up control over the shop floor and gave up control over management investment decisions. Then that Treaty of Detroit pattern basically set the pattern for the post war period where labor basically abandoned its broader vision of trying to play a broader role in shaping the economy.

And while this is just one plant and one union and one contract, what we’re seeing with the move to use the collective bargaining process to force the company to reopen a plant, what I was saying in the article is that this marks an effort to reassert that broader vision for labor and trying to infringe on what has been management’s sovereign right to manage, that we will take care of wages and benefits for workers and some basic grievance procedures and stuff like that, but we relinquish any claims on being able to have a say in investment decisions. And so this is a step away from that and back towards the broader vision. And it’s important to recognize that these plant closings have a devastating impact on communities, right? The company justifies these plant closures by referencing their company’s profitability and other opportunities for investment and it’s sort of this dollars and cents, bottom line calculation with absolutely no consideration, or very little consideration for the path of destruction that these plant closures leave in their wake, or these entire communities that are left devastated, these families that are torn apart. And so I think that reshaping the narrative around who has a right to intervene in company investment decisions, do the people who are going to be directly affected by these company investment decisions have a right to have a say in those investment decisions? And I think that kind of question is now back on the table in a way that it hasn’t been in many decades.

Teddy Ostrow: Another element of the tentative agreements that may be representative of a greater shift in the union is that the contracts, if they’re ratified, will now expire on May 1st or the day before, which is the international holiday of May Day.

And one could say this is perhaps symbolic, but it also is quite strategic, I think. UAW President Shawn Fain has called on other unions to basically line their own contracts up to expire on that day as well. Can you give us a very brief crash course on the importance of May Day, basically so you can help us understand why the union did this, and what it says about the kind of unionism the UAW is trying to influence across the labor movement?

Barry Eidlin: Yeah, I mean, there are practical considerations, just that having the contract expire at the end of April means that workers are on the picket lines in the spring and summer instead of in the wintertime, which is non trivial when you’re talking about a protracted strike situation.

But it’s really the symbolism that’s important here. And I don’t mean symbolic in the sense of meaningless. I mean symbolic in the sense that it means something really important. So May Day obviously is the international workers’ holiday. Some people sort of say that it’s the real Labor Day and that the one in September is the fake Labor Day, but I think we should just have two Labor Days and we should fight for more Labor Days, as far as I’m concerned.

But May 1st is considered this worker’s holiday. It is to honor the martyrs of the Haymarket massacre on May 4th, 1886. I’m not quite sure what the history is of why it shifted from May 4th to May 1st, maybe it has to do with the Pagan holidays of May Day in Europe, I’m not quite sure.

But in any case. In 1887, some members of the Socialist International decided that they were going to designate May 1st as a workers’ holiday, and it sort of held that position ever since. And there’s been efforts in the U.S. to sort of recapture May Day, even though it originated in the U.S. has never really been as big of a holiday that it is in other parts of the world. So there have been efforts recently to recapture that.

But what’s important here with the UAW aligning their contracts to expire on April 30th, with the strike beyond May 1st and inviting other unions to do the same, to align their contracts, it really speaks to Shawn Fain and the new UAW administration’s commitment to a more class struggle vision of unionism, right? That’s really the story of the UAW contract campaign and the Stand-Up-Strike that ensued, is one of developing a much more explicit framework of class warfare, and that we are fighting not just for auto workers, but for the entire working class, that we are engaged in a class struggle with our billionaire class enemies, drawing these clear dividing lines and mobilizing workers around this broader vision.

And so aligning the contracts to expire the day before May Day and then inviting others to do so is a concrete embodiment of that broader vision, right? It sort of is a way to turn that vision into reality because it creates the structural preconditions for having a mass strike on May 1st of 2028 in a way that is, I mean, you will often hear small groups on the left talk about calling for a general strike and it’s sort of in the realm of fantasy, this actually brings that into the realm of a very real possibility, especially if we see other other unions follow suit.

Teddy Ostrow: Right. I remember when I first heard that they are extending the collective bargaining agreement length, before I understood why I was like, oh, usually you want a shorter contract sometimes. And then I understood. No, this is a way to sort of align the labor movement together. It’s another one of those first steps towards influencing a change in the broader movement for the wider working class in the United States.

Barry Eidlin: Yeah, I think so basically. And, and then you ask, well, why is it four and a half years instead of three and a half years?

And I think that what you’re getting at there is really important to keep in mind is that there’s some groundwork that needs to be laid in the next few years, both to get other unions on board with this vision, but also as Fain discussed when they were announcing the contract details to do a lot more to reorganize the U.S. auto industry in the next few years so that the next round of negotiations is fundamentally different.

Teddy Ostrow: That’s a perfect transition to my next question, which is, we’ve talked a bit about this on the podcast, but the Big Three contract fight this year has always been about more than just the Big Three. It’s also about how this sets the UAW up for an existential task, that is, organizing the non union auto giants so that we’re talking about a Big Five, a Big Six. Like Toyota, Hyundai, Volkswagen, Nissan, and of course, Tesla. We saw reporting from Labor Notes that’s now been reported elsewhere as well that Toyota responded to the TAs by raising workers wages and also shortening the progression to top rate. And this was presumably to sort of blunt any desire by workers to unionize their workplace. This is like a common trend that we see across different workplaces and sectors. But also we saw reports from Bloomberg that workers at the flagship Tesla plant in Fremont, California have formed an organizing committee with the UAW.

So I’d like to ask, maybe give us a little bit of background. You know, what is the UAW’s recent track record in organizing these mostly, but not all, foreign auto plants? How might these TAs have changed the environment for the union’s organizing potential? And then also, of course, maybe you should explain to listeners why their ears should perk up a little bit, when they hear that the UAW has set its sights on that Fremont Tesla plant.

Barry Eidlin: Yeah, so I think that what Toyota did is what these so called transplants, these quote unquote “foreign owned companies”, and I say that because, nowadays, the idea that the Big Three are American auto companies is questionable at best. Especially Stellantis, which is headquartered in Amsterdam, I think. I forget. Not the U. S.

But the UAW has failed to organize transplants ever since they started arriving in the U.S. And one of the ways that the transplants have fended off unionization is by matching some of the basic wage packages, at least, of the UAW, and so they’ll give them similar wages.

They won’t get the pensions and the healthcare and stuff like that, but the basic wage rates would be the same and that would often be enough to sort of placate people. And in recent years, the transplants just haven’t had to do much of that because the UAW was giving concessions.

So UAW plants were in many cases, workers in those plants were doing worse than people in the transplant. So there’s no organizing threat there, right? Because why would you join a union to bargain concessions for you, right? There’s just no logical reason for it.

So what Toyota is doing now is sort of a return to past practice in that sense. But I think what we need to be thinking about now is that, now there is a real threat of more organizing and trying to sort of change the balance of power. And I would be much more focused on the sort of bigger automakers like Toyota, Honda, Hyundai, stuff like that, rather than focusing on the Tesla plant, even though, you know, I did tweet out that, I think that it would be hard to think of a single organizing victory at a single shop that would have the kind of symbolic meaning and substantive meaning of organizing Tesla.

The problem there is, in academia, if you’re sort of in labor relations and you take a collective bargaining class, there’s this thing called BATNA, which is the Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement. And the problem is that in the case of Tesla, Elon Musk’s BATNA is destroying the company.

He would rather have Tesla disappear than be a union company. He would rather just throw it down the garbage disposal. And if that’s the employer’s BATNA, you’re not going to be able to organize the plant, especially when you’ve got a billionaire with the resources, you know, so as much as I would love to see that, I don’t think that’s the wisest use of the UAW’s resources at this point, whereas you do have these other plants to organize that are very much invested in staying in the U.S. and want to capture market share in the U.S.

One of the things that’s important to keep in mind for your listeners here in this broader context is that despite all the rhetoric of deindustrialization that we’ve heard over the past several decades, the auto industry in the U.S. is still quite vibrant. As I wrote in that Belvedere article, the proportion of the workforce employed in auto, in 2022 is basically the same as in 1983. So we haven’t had auto jobs disappear in the U. S. in the way that we’ve seen, like steel jobs disappear, or textile jobs, for example. Auto jobs, we still make a lot of autos and auto parts in the U.S., it’s just that the sector has been de-unionized. So while the percentage of employment stayed roughly constant over the past 40 years, unionization rate dropped from roughly 60% to 16%.

And that’s because of these transplants that are all non union, the Big Three automakers spinning off their parts plants and others into these non union subsidiaries, all these layers of subcontracting and so on. So the story in auto is not de-industrialization, it’s de-unionization.

And that’s a very different challenge that’s much more tractable. It’s much more, it’s a much more of a doable challenge for the UAW. That’s not to say that it’s a walk in the park by any stretch. Organizing these plants is a huge challenge. But these plants are here. The work’s not all going to Mexico and China like the deindustrialization rhetoric would hold. These companies are in many cases reshoring, they’re bringing more work into the U.S. So that creates this target-rich environment for organizing, basically, but the job is to essentially re-organize the US auto industry, and that’s going to be essential to any long term strategy for maintaining the UAW as a going concern in the coming decades.

Teddy Ostrow: To close out, I want to ask you a somewhat tangential question. You and I have discussed on this show two very important union battles, many of us have considered them to be of this earth shattering importance for the labor movement—the UPS Teamsters and the Big Three auto workers, and you’ve laid out those cases very well.

I’m curious though, moving into 2024 in the United States, where are your eyes and ears moving next? Is it another shiny contract expiration? Is it another sector of the labor force? Should we even be thinking about it in this way? Is it new organizing? Just what should listeners be following in the world of labor, after the UAW contracts are eventually ratified?

Barry Eidlin: Yeah, that’s a really good question. One of the things that’s kind of exciting, but also confusing about the time we’re living in is that it’s hard to know where it’s going to pop off next, precisely because we’ve seen these strikes and contract fights in all different sectors across the economy, right?

It’s not like in 2018 where it was like education workers and you have the red state revolt, which everybody got excited about, but it was really just contained to the education sector for the most part. Nowadays, we’re seeing healthcare, we’re seeing Hollywood, we’re seeing grocery. We’re seeing longshore, you know, we’re seeing academic workers. It’s really kind of all over the place. So there is this kind of contagion effect, and it’s hard to know where that’s going to build up to. There isn’t the same kind, I mean, certainly on the scale of UPS and the Big Three next year, I don’t see anything on that scale where we can just sort of pinpoint that and say, okay, we need to watch that contract.

But there’s going to, there’s definitely going to be part two of the Hollywood battles, so this year it’s been the actors and writers and the next year it’s going to be the people below the line, people who do all the grunt work that makes Hollywood work, who are represented by IATSE. And the Teamsters are going up for their negotiations and I suspect that’s going to be a pretty significant, throw down and then it’s also going to be spiced up by the fact that you’ve got Teamster Western region vice president and motion picture director, Lindsay Doherty, leading the negotiations for the Teamsters.

So that’s certainly going to be something to watch, both for the substantive importance and the entertainment value, And I think, I believe the postal workers are going to be coming up fairly soon, and, we’ve got Mark Diamonstein in charge of the postal workers there.

I think that’s going to be a big fight. So, there are a couple of those, but I think the big thing is just to see whether the momentum and energy that we’ve seen from hot labor summer turn into fiery labor fall. I keep on trying to make that happen. It’s happened to me. We’ll need to come up with a winter one, you know, winter is coming, to see whether that keeps on building. Right. And I think, you know, that’s the question that people always ask me is, like, is, are we in an upsurge? And I keep on saying, there’s a bit of an uptick. But what I will say is that, if we are, if we’re sort of sitting here a year, two years from now in a bona fide upsurge of the type that we saw in the sixties and seventies or in the thirties and forties, that the key necessary elements for that upsurge were taking shape in the time that we’re in right now, and the fundamental condition for the upsurge, if it happens, is this layer of worker led organizing, and we see that taking shape, the headline grabbing stuff at Starbucks and Amazon.

But the organizing that led to the contracts with the teamsters in the UAW was only possible because of the rank-and-file organizing of Teamsters for a Democratic Union and Unite All Workers for Democracy. These rank-and-file movements, you have these workers in other sectors who are rejecting their contracts and pushing for something better.

So there’s a whole layer of independent worker-led organizing that is essential for it because you can’t sort of staff your way up to a labor upsurge. And so that layer of worker-led organizing has to expand and grow if we want to see what we have now actually develop into something more like a true upsurge.

So that’s really the thing that I’m going to be watching more than anything.