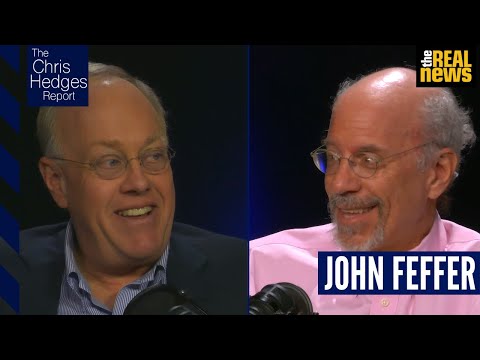

In his dystopian novel Splinterlands, John Feffer looks ahead to life on planet earth in the year 2050. The signs of societal breakdown in the not-so-distant future, if we look, are already apparent in our world today. Feffer follows them to their logical conclusion. The climate is at war with the human species and every other species. The European Union, overrun with climate refugees, has disintegrated. China and Russia have folded in on themselves, as has the United States, where fractious and violent militias and gangs battle over diminishing resources. Splinterlands, with wry, black humor, is told by the octogenarian geo-paleontologist Julian West, mortally ill from one of the latest pandemic variants. This is a Mad Max world of water wars, imitation foods made from seaweed, inequality, disease, and sleeper terrorists. In the latest installment of The Chris Hedges Report, Chris speaks with Feffer about his trilogy, the climate crisis, and where we are headed as a species.

John Feffer is co-director of Foreign Policy In Focus at the Institute for Policy Studies. He is the author of numerous books, including Aftershock: A Journey into Eastern Europe’s Broken Dreams and the dystopian fiction trilogy Splinterlands, Frostlands, and Songlands. His writing has been featured in a range of outlets, including The New York Times, Washington Post, USAToday, Los Angeles Review of Books, and Salon.

Chris Hedges interviews writers, intellectuals, and dissidents, many banished from the mainstream, in his half-hour show, The Chris Hedges Report. He gives voice to those, from Cornel West and Noam Chomsky to the leaders of groups such as Extinction Rebellion, who are on the front lines of the struggle against militarism, corporate capitalism, white supremacy, the looming ecocide, as well as the battle to wrest back our democracy from the clutches of the ruling global oligarchy.

Watch The Chris Hedges Report live YouTube premiere on The Real News Network every Friday at 12PM ET.

Listen to episode podcasts and find bonus content at The Chris Hedges Report Substack.

Pre-Production: Kayla Rivara

Studio: Adam Coley, Cameron Granadino

Post-Production: Cameron Granadino

TRANSCRIPT

Chris Hedges: John Feffer, in his dystopian novel Splinterlands, looks ahead to life on planet Earth in the year 2050. The signs of this breakdown, if we observe what is happening, are already apparent. Feffer follows them to their logical conclusion. The climate is at war with the human species and every other species. The European Union, overrun with climate refugees, has disintegrated. China and Russia have folded in on themselves, as has the United States, where fractious and violent militias and gangs battle over diminishing resources. Because Washington, DC, was destroyed by a hurricane and is underwater, the nation’s Capitol has been relocated to Kansas City. Splinterlands, with wry, black humor, is told by the octogenarian geopaleontologist Julian West, mortally ill from one of the latest pandemic variants. He is battling what time he has left to write the follow-up to his best-selling 2020 monograph, also called Splinterlands, in which he analyzes the social, political, and environmental disintegration.

This is a Mad Max world of water wars, imitation foods made from seaweed, inequality, disease, and sleeper terrorists. West, in the book, takes one last virtual reality trip to make amends with his children: Professor Aurora in a deteriorating Brussels rampant with kidnappings; wealthy opportunist Gordon in Xinjiang, no longer part of China, and his estranged son who is a mercenary in prosperous Botswana. His ex-wife Rachel, who he also visits, lives in a commune in Northern Vermont, now lush with orange groves and a climate that resembles Southern California.

Joining me to discuss his book and where we are headed is the novelist and playwright John Feffer, co-director of Foreign Policy and Focus at the Institute for Policy Studies and a fellow at the Open Society Foundations. And I should also add, playwright. But let’s begin. Because I love the book, as I told you. I thought the footnotes were hilarious, having spent a lot of time with pedants who actually hate the subject they wrote their PhD on. But they’re very funny. Don’t miss them when you read the book, which is beautifully written. But let’s talk a little bit, because you really begin with the fissures that are already around us.

John Feffer: That’s correct. It was an extrapolation, a worst-case scenario, if you will, but also cautionary. This is a book that is not designed to glory in the horrors, but to send a message that unless we address these horrific trajectories that we are on, we will continue down them toward the necessary end point. It’s not too late. I mean, that is another message from the book. We can address climate. We can address the worst ravages of nationalism. We can address political polarization. Of course, the book doesn’t provide us with a blueprint on how to do so, but there are two other volumes in the trilogy that attempt, at least in some small way, to explore those other opportunities and alternatives.

Chris Hedges: But yet the forces that have us in their grip, these corporate forces – Which, I’m not going to ruin the end of the book, but certainly determine the life of the protagonist. These are forces that are bent on exploiting the crisis and, in many ways, exacerbating it.

John Feffer: Absolutely. But of course, they don’t see themselves as that. They see themselves as saving the world. Now, how they define the world is an entirely different matter. Because this particular corporation, which is called the CRISPR corporation, devoted to genetic editing, sees itself as saving a small portion of humanity, the richer, shall we say the 1%, and giving them an even longer lifespan. But in order to do that, well, the resources are not available, of course, to save all of humanity, so they have to be rather ruthless about some of the policies and some of the drugs that they manufacture. That leads us to, of course, the denouement of the novel itself.

Chris Hedges: What you’re really describing is a kind of third world environment that envelopes all of us. I live, for instance, in Lima, Peru in Miraflores, which looks like Miami, except the walls are higher and have concertina wire. 10 blocks away, shantytowns are crowded around open sewers without running water and electricity. I think that’s right, that you have these kind of gated compounds where people have access to security and water and food and medical assistance, and then outside those gates, it’s kind of the world of the proles.

John Feffer: Unfortunately so. In part, that’s because, you know, the lifestyle of the middle class, of the Global North, if you will, is frankly unsustainable. We cannot live according to our means as we have defined them, given the resource base of this planet. Now, either we decide in some rational way to distribute the wealth in a fair and equitable manner, or we will see our Global North reduced against our will, so to speak, and brought down to the level of the third world, of the Global South, with the exception of these compounds of the rich. Now, in the book itself, there’s an irony here, of course, because the compound that we are most familiar with in the book is called Arcadia. It seems like the best of California progressivism. It is growing its own food. It has a cooperative kind of political structure.

Chris Hedges: We’re talking about Vermont?

John Feffer: Exactly. In Northern Vermont.

Chris Hedges: They also have an arsenal.

John Feffer: Exactly. They have an arsenal because in this world of diminishing resources, it’s dog eat dog. There are a lot of contending forces that are well-armed. That if they see that you have food, if they see that you have security, they are going to target you. So Arcadia is very well-armed and willing to defend itself.

Chris Hedges: I was born in St. Johnsbury and my parents lived in Barnet Center, which is exactly where this is located. It’s on the border with Canada. You have, I think, armed groups of Quebec separatists making border crossings.

John Feffer: That’s right. That’s right. As you said, the United States has basically fallen apart. All of the fissures that we see today have simply grown wider. And they’re not just political fissures. I mean, these are also geographic features. California has broken away, Pacific Northwest. We see that today buried beneath the headlines. We see that there has been separatist groups that have emerged in Texas that would like to go off and create their own Red Republic, as well as the bluest of blue in California that would like to create what they think of as a progressive utopia, all of which contributes to a fragmenting of the United States very similar to the fragmentation of Yugoslavia in the 1990s.

Chris Hedges: Of course, I was there. Those were broken down along ethnic lines. These are broken down around what lines?

John Feffer: Well, they’re broken down largely along political lines, because this is the United States where we have had these culture wars and pitted battles between political tendencies now for several generations. They’ve, of course, become accentuated during the Trump years. But here in this book, we are seeing a kind of pitched battle between the left and the right, between blue states and red states, between conceptions of what the national government should be, what the federal government should be. In other words, extreme libertarians who do not want the federal government in their lives, and those who are still wedded to some sense of national unity, however they understand that. And that ultimately becomes the biggest dividing line here in the United States.

Chris Hedges: I want to ask whether it is between red states and blue states, or whether it’s between rural and urban. I covered the war in Yugoslavia. In fact, if you looked closely, the conflict was between rural and urban.

John Feffer: That’s absolutely true. That’s been updated into the modern era or the post Cold War era into what I’ve extrapolated from the expression Poland A and Poland B. Poland A and Poland B is how the Poles refer to the divide largely between urban and rural that has emerged between those who have benefited from the reforms that have taken place post-1989 and those who have not. Yes, there’s an urban elite that have done very well as a result of privatization and other neoliberal reforms in the country, and then there are the folks who used to work in factories in the countryside. They’re small farmers. They’re retirees and pensioners, and have not done very well at all. That divide has produced a conservative backlash in the country. The Law and Justice Party have been in power now for several years.

We see a similar divide in Hungary between Hungary A and Hungary B, again, between those who have benefited from the liberal policies and those who haven’t. I would say that, frankly, we have seen that at a global level. There’s globalization A and globalization B, those who have benefited from globalization, which, to a certain extent, is neoliberalism writ large, and those who haven’t. We have the same phenomenon here in the United States. A tremendous number of people feel as if they simply have not benefited from what has been billed as the greatest economic recovery, say, from the financial crisis of the late 2000s. They haven’t seen those benefits. They may not be unemployed, but they’re working two, three jobs, very difficult to make ends meet. So yes, this conflict between urban and rural is, I think, far more important than blue state or red state, because we see it within states as well.

Chris Hedges: Well, in fact, life is worse. I mean, my mother’s family all comes from rural Maine, and these towns are decayed ruins. The mills are all gone. You talk about political apathy. You write, “The electorate collaborated in its own disenfranchisement. In the public’s view, all politicians were corrupt, all civil servants inept, and every government little more than a mafia plus an army. Once the public had been persuaded to cut the state down to size, the real mafias took over.” It reminds me of Karl Popper, who wrote that first you have a mafia economy, and then you have a mafia state.

John Feffer: Yeah. I mean, I wish I could say it better than I wrote it, but…

Chris Hedges: I thought that was all right.

John Feffer: But yeah, this is a concern that people are seceding from society. That’s what apathy has amounted to in the last generation or so. They no longer see themselves as part of a commonwealth. They no longer see government as a representation of us. It’s rather a representation of them, of the looters, of the corrupt. Of course, it’s not just a phenomenon here in the United States. Why did Bolsonaro win in Brazil? I mean, the critique of mainstream politicians and of politics in general has led to an enormous secession. That secession is economic to boot. I mean, for instance, people have seceded from public education. They send their children to private schools. They have seceded from the communities. They do as much as they can to avoid paying taxes. They build their own private garrisons, huge gated estates with security forces. Again, something we are familiar with in the Global South, but increasingly so in the United States as well.

So this secession from society is an extraordinarily troubling phenomenon. It’s often described as simply apathy, political apathy, but that doesn’t quite get at the potential violence and aggression that this secession really amounts to.

Chris Hedges: I’m going to read one of your footnotes. My favorite part of the book are your footnotes. You write, “The debate over the so-called clash of civilizations obscure an essential point. Most of the clashes in the Middle East,” I spent seven years there, “were taking place within civilization.” I thought that was actually a pretty important point.

John Feffer: This was a major critique, of course, of Huntington’s thesis of Clash of Civilizations when it came out, that here were seven or so major civilizations, and that the primary wars were occurring along the fault lines between these civilizations. But in fact, that never made sense. I mean, if you looked at the Islamic world, the Islamic world was hardly a unified civilization, with Shia and Sunni fighting against one another, but you could find the same kind of fissures throughout these so-called civilizations. It obscured a very important set of debates that were taking place, often violent debates that were taking place in the Global North as well as the Global South. It obscured these debates.

It was ultimately like Fukuyama’s End of History, a thesis that was so wrong on the face of it that you had to ask yourself, well, why are people investing any kind of authority in these statements? There has to be some other reason, because on the face of it, it has no intellectual legitimacy. Therefore, it must represent something else. It must signal, somehow, a deep anxiety on the part of thinkers and politicians, anxiety about what’s happening in their societies that they are averting their eyes from. And this becomes a kind of compensatory mechanism in some sense, an intellectual construct that they can invest their hopes and dreams and their intellectual credibility to avert the gaze, their own and the gaze of their followers, from what’s really happening underneath societies.

Chris Hedges: It also fuels this rampant militarism. You know, our civilization, which of course is posited as superior, must dominate the barbarians. It didn’t end up too well for Rome.

John Feffer: No. There are a couple of very interesting books that have come out recently about the so-called liberality or liberalness of the English Empire, that somehow the English empire was more liberal, more tolerant, more progressive than its other colonial competitors, whether we’re talking about the Belgians in Congo or the Spanish, the Germans, the French. But that wasn’t, in fact, true. I mean, the British were just as violent. They were the ones that expanded on the notion of concentration camps. They came up with surveillance systems, torture. They were extraordinarily brutal, and they actually produced a violent legacy that they passed on to post-colonial states.

But this notion of British liberality that is so wonderfully described, if you can put it that way, by Niall Ferguson in his books on empire was completely bogus. So it did, in the same way, obscure the violence that lay beneath imperial conduct in the same way that our supposed liberality here in the United States or in Western Europe also obscures much of the violence that we’re perpetrating. And again, not just in Afghanistan or Iraq, which are the obvious places. It’s the easiest places to see. But violence in a structural and systemic way within our own societies.

Chris Hedges: Well, this is the mantra of the neocons, liberal interventionists, from Samantha Power to Robert Kagan to… What do they call it? Benign hegemony or something.

John Feffer: Yes.

Chris Hedges: But it’s of course completely untrue. You’ve spent many years abroad, as have I. I’ve spent 20 years reporting on the outer reaches of empire from Central America to Iraq. You target the year 2023. I always find this very brave. “When the dollar fell from its perch as a global currency, the US government went into receivership, and its vast overseas military footprint became unsupportable.” Alfred McCoy and others have cited, we know what happened to the British empire when the pound sterling was removed as the world’s reserve currency in the 1950s. It’s not conjecture, but it is an important point. Perhaps you can discuss it.

John Feffer: Sure. I mean, first I’d say, back in 2016 when the book was published, 2023 seemed impossibly far away. So I could safely make all sorts of predictions. You know, I’ve written about futurologists and the dangers of futurology, none perhaps more salient than George Will’s prediction that the Berlin Wall was going to live forever, which he wrote two or three days before the Berlin Wall fell, but which was published, I think, actually afterwards, much to his chagrin.

Chris Hedges: Well, that’s like Lenin. Lenin will never see the revolution in our lifetime or something, then six weeks later.

John Feffer: Exactly. So back in 2016, of course, I set the book in 2050. I thought, well, I’m safe there. But we had to put in some events between 2016 and 2050. 2023 seemed safe enough. The hegemony of the dollar, well, I thought that maybe in the 2020s we would see this, in part because there were expectations that the Chinese economy would at that point surpass the United States both in real value but also just in terms of its size, that the huge debt of the United States would finally start to bear fruit, poison fruit in this case. So I thought, 2023, that seems like a reasonable date that the mechanism by which the United States has basically maintained its hold over the global economy and through the supremacy of the dollar, that this would come to an end. It wouldn’t necessarily come from one day to the next, but it would be a kind of gradual overtaking of the dollar by a basket of currencies, whether it’s the euro or the yuan. Of course, I didn’t anticipate that cyber currencies, cryptocurrencies would become important.

But to understand the mechanism of US decline, I think you really have to understand how the United States has maintained its perch through its control of the global economy. It’s not just the currency, of course. It’s through our control, our hegemony, if you will, in the IMF, in the World Bank, over international institutions, how we write the rules. And if you write the rules, well, you can write those rules to benefit yourself.

Now, at the time, I didn’t think that China would actually be constructing its own parallel international economy, effectively. In those early days, we saw the Belt and Road Initiative emerging from 2013 on, but at that point I still thought, well, there’ll be a competition, and China is aspiring to have more say, for instance, in the World Bank and the IMF. It’s building up the bricks as a kind of unified effort to challenge the United States. I didn’t think that China would go to such lengths to create its parallel economy. I think that, ultimately, will prove the decisive factor in terms of the unseating of the United States. Because it will be China writing the rules, effectively, and the sphere that it creates simply enlarging. And –

Chris Hedges: Well, the dollar will clearly drop in value significantly.

John Feffer: Yes.

Chris Hedges: The treasury bonds, which sustains the debt, will no longer be attractive as an investment. I mean, it would be devastating.

John Feffer: Yeah, absolutely. The bill will come due. You know, we can talk about in terms of carbon footprint, in terms of the United States living unsustainably, but even before climate change became an issue and we were all obsessed with carbon footprints, it was clear that the United States was living beyond its means, that we American citizens, each and every individual, was kind of drawing on the global resources at a far faster rate than anybody else in the world, and that this was simply unsustainable. Unsustainable not simply from a climate point of view, but unsustainable in terms of the rest of the world’s people accepting it.

We have been challenged, obviously, by even our European competitors. But it was really going to be India, China, Brazil, populous countries in the Global South that are simply going to say, no. Not going to allow American citizens, we’re not talking about the government per se, but American citizens to draw so much. It’s like drawing from groundwater, and everybody else has tiny little narrow straws, and we have a Big Gulp straw and we are just drawing it in huge quantities, and the rest of the world is simply not going to take that.

Chris Hedges: So this is a description which seems pretty current. “Domestic politics remain divided as Congress and the executive branch congealed like two pots of cold oatmeal. Neither they nor the various states of the Union could establish a consensus on how to re-energize the economy or reconceive the national interest. Up went hire walls to keep out foreigners and foreign products. With the exception of military affairs and immigration control, the government’s role dwindled to that of caretaker. The country experienced an epidemic of mega assault rifles, armed personal drones, and weaponized biological agents, all easily downloaded at home on 3D printers. Though many refused to acknowledge the trend, our society drifted into a condition closely approximating psychosis, and increasingly embittered and armed white minorities seemed determined to adopt a scorched Earth policy rather than leave anything of value to its mixed race heirs. Today, of course, the country exists in name only, for the policies that really matter are all enacted on a local basis.” That’s clearly where we’re moving.

John Feffer: Unfortunately. I was influenced, I think it was around the time I was writing this, when Obama said, I should not have been elected in 2008. That was a fluke. The only shot I had, demographically speaking, in terms of the transformation of the electorate, would’ve been in 2028. I thought about that deep and hard, because it was clear that the Republican Party was a minority party, that it was clinging to power by various mechanisms to forestall the day that a Barack Obama could be elected. Again, he was elected earlier than anyone anticipated, or a Barack Obama figure was elected earlier than anyone anticipated.

But the question is, much like our discussion of the United States and whether the United States is willingly going to give up its global hegemony, is the Republican Party going to be willingly giving up its political hegemony within the United States? Increasingly, as we’ve seen, it’s not willing to do so, much as the several figures including Trump himself and the Trump administration said they were not going to willingly depart office even if they lost the election in 2020.

So to what lengths will the Republican Party and Republican Party supporters go to maintain their control over the American political machinery, the American economic machinery? This book, in some sense, is a projection of what a beleaguered white minority will do. It will go to such great lengths that it will destroy the country in order to save the country. Of course, we’re familiar with what US governments have done in the past to save other countries by destroying them, obviously Vietnam, but its own country? Republicans or the beleaguered white minority would destroy its own country? Well, that wouldn’t be its ambition, but that would be the consequence of its policies.

Chris Hedges: Well, that’s the disease of empires. Thucydides says the tyranny that Athens imposed on others it finally imposed on itself, destroying the Demos. You write, “I made the mistake of thinking that climate change was out there already,” and this is Julian West, “like avian flu or nuclear weapons, a potential vector, a future destruction rather than a fundamental disorder at the heart of the modern system. In fact, climate change was re-engineering the very DNA of the global order. Water wars helped split China apart; energy conflicts remapped the Middle East, Central Asia and Africa, arable land became so precious that several rich agricultural regions: Brazil, Java, and Indonesia, secured their independence in order to fence off the [territory].” We’re also watching exactly that phenomenon.

John Feffer: Yeah. I should note that the excerpts you’re reading suggest that this is a manifesto rather than a novel, and that has been an interesting tension within the book itself. Because here’s a guy, Julian West, who has a lot to say. I mean, he has an ax to grind. He is trying to demonstrate that the thesis that he made in 2020 in his monograph was correct. So he’s revisiting this and explaining himself once again. He is, of course, an unreliable narrator, as we discover through the footnotes. The tension in the book in some sense is, well, if he’s unreliable about his own personal history, is he unreliable about everything else as well? So there are some suggestions that, well, maybe his analysis wasn’t entirely correct. So that’s a challenge.

But what you’ve read? Yes. I would subscribe to that, as the author of the book. Climate change has proven to be a symptom rather than the problem itself, a symptom of, frankly, the growth mechanism that we’ve all subscribed to as part of a variety of different ideologies. I mean, growth at all costs was as much part of the DNA of capitalism as it was of communism, of communism as it was of capitalism. It is the natural result of digging up every mineral, mining every possible energy source, unleashing every entrepreneur to do whatever he or she wants.

Chris Hedges: Well, fracking would be a perfect example.

John Feffer: Exactly. Climate change is just one of the symptoms of this pernicious trajectory embedded in our economic ideologies. There are plenty of others: air pollution, the destruction of communities. I lay them out in this book to understand that Splinterlands, the splintering of countries, of communities, is not simply the natural kind of result of nationalism, of extreme nationalism, that we can blame it on, say, the Le Pen’s of this world, the Viktor Orban’s of the world. Yes, they are the agents, perhaps, but there’s something more fundamental going on that’s producing this splintering that we see in our midst today. I mean, we don’t have to wait until 2050 or 2025 to see this splintering. These mechanisms implicit in our economic and political organization are what is driving people to secede from societies, from societies to secede from larger organizations, larger organizations to secede from states, states to secede from the EU, et cetera, et cetera.

Chris Hedges: Well, great. As you point out, and it’s in the title, the breakdown’s non-linear. I think that’s what you get completely.

I want to thank The Real News Network and its production team: Cameron Granadino, Adam Coley, Dwayne Gladden, and Kayla Rivera. You can find me at chrishedges.substack.com.