I remember, as a kid, hearing a story about a lone man, a mortal man, who had traveled to the underworld. He was a great warrior, and his name was Er. “He once upon a time was slain in battle,” Plato writes, “and when the corpses were taken up on the tenth day already decayed, his was found intact, and having been brought home, at the moment of his funeral, on the twelfth day as he lay upon the pyre, he revived, and after coming to life related what he had seen in the world beyond.”

Like a lot of kids, I was drawn, almost hypnotically, to all kinds of mythology: Greek mythology, Egyptian, Aztec. I had no firm sense of what “mythology” really meant, nor the negative connotations it had in the eyes of the adult world, the “modern” world, the “enlightened” condescension with which grownups mentioned the term. To me, much like the Bible, these were historical records, stories of worlds and people and gods and monsters that had all existed at some point… a long time from now, a long way from here. They were real to me.

And I remember, somewhere in the softest parts of my young brain, being absolutely haunted by this story. I was afraid to even walk into our garage at night. I couldn’t help but imagine myself walking into the blackness down there, at the edge of oblivion, into a hopeless abyss of endless pain. Imagine yourself literally, not figuratively, going to hell and back. How, I thought, could anyone endure that? How could someone as real as me, my siblings, or my parents, someone real enough to hurt as much as I knew real people could hurt, someone who was a kid once, too, like I was—how could they survive that experience? How could they bear the weight of everything they saw? How could they possibly be expected to communicate that experience to those who could never truly understand? How would that person be in daily life, how would they relate to other people after everything they had been through?

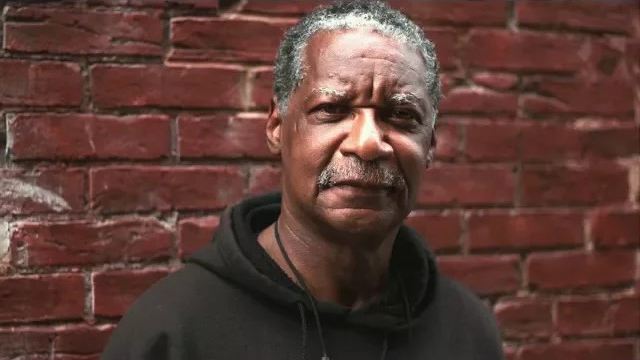

I have been forever changed after witnessing firsthand that Eddie, the Er of our time, bore all the weight of the underworld not with the crushing bitterness and disfigurement of the soul that I expected, but with unimaginable kindness, with a fierce and undying love for others, and with an unwavering commitment to the struggle to fix the world that had so unforgivably wronged him.

I never could have imagined that, decades later, the fates would be so kind as to give me answers to these questions when I was fortunate enough to cross paths with Eddie Conway. And I have been forever changed after witnessing firsthand that Eddie, the Er of our time, bore all the weight of the underworld not with the crushing bitterness and disfigurement of the soul that I expected, but with unimaginable kindness, with a fierce and undying love for others, and with an unwavering commitment to the struggle to fix the world that had so unforgivably wronged him. I never could have conceived that I would get the opportunity one day to hear him tell the story of hell that us fellow mortals need to hear, and to help him and our team at The Real News Network do that vital work. And when Eddie told that story, people listened. Because he didn’t just tell it himself—he committed himself, always, to lifting up the voices and struggles of those who have not only been victimized by, but who are themselves in the struggle to storm the gates and dismantle the man-made hell that is white supremacy, patriarchy, imperialism, and the monstrous, people-swallowing machine of the prison-industrial complex. Even now, as my heart breaks in unison with all who knew and loved him, I can hear Eddie in my head, speaking with all the tenderness of encouragement, but with all the seriousness of a command: Don’t stop doing this work, and never forget who we’re doing it for.

Even now, as my heart breaks in unison with all who knew and loved him, I can hear Eddie in my head, speaking with all the tenderness of encouragement, but with all the seriousness of a command: Don’t stop doing this work, and never forget who we’re doing it for.

Eddie was one of the main reasons I left my old job, in the middle of a deadly pandemic, to come work at The Real News. And in many ways, he is the reason I am still here. I took that leap in October of 2020 because, like Eddie, I believed in the mission of what we do here at TRNN, I believe that making media can and must play a vital role in the unending struggle for liberation, for a more just world, and for a future worth living in. But I came to TRNN specifically for the people at TRNN, present and past, people like Eddie, people like Mansa Musa, people like Cameron Granadino and Ericka Blount, and so many others, because they are the ones who have always made the mission something real, tangible, worthwhile—more than just words. Then, precisely one month after I started here as editor-in-chief, like many other media outlets, the financial shock of COVID-19 hit us hard, we lost a significant portion of our funding, and we lost half of the staff I had explicitly left my old job to come work with here. “Jesus,” I thought, “what the hell did I just walk into? What the hell are we going to do now?” I won’t lie, in the darkest moments during that very dark time, I wanted to leave. I never admitted that to anyone on our team, but Eddie was the one who heard it in my voice. When we spoke on the phone for the first time after we got the news, the first words out of his mouth were, “How are you holding up?” I was honest with him… there was no way not to be your most honest self when you were talking to Eddie.

“It’ll be alright, man,” he told me. “You and me, we soldiers. We can’t stop, and we won’t stop.” I’ll never forget that.

Eddie was a caretaker. He took care of us. He took care of everyone who passed through The Real News.

Eddie was a caretaker. He took care of us. He took care of everyone who passed through The Real News. Everyone I’ve spoken with, everyone who currently works or has worked at TRNN, has shared with me a version of the same story: they have told me that Eddie was their rock, he was their calm, he was their protector, the one who was always there to talk when they were feeling overwhelmed, when they were sad or frustrated, when they too were thinking of leaving, when the stress of the work was so intense that they could no longer remember why this work was important. We have come a long way here to rebuild TRNN in the past few years, and I realize now that, if it weren’t for Eddie, we would have had nothing and nobody to rebuild with. I will forever be grateful to him for that, for taking care of our people, and I have never been more committed than I am now to carrying on the work he believed in, and we will do that work in a way that would make him proud.

Eddie’s memorial service was held in Baltimore on Feb. 25, 2023. That was the first and only time I ever “met” Eddie in person, the first and only time we were ever in the same physical space together. Obviously, between COVID and dealing with the immeasurable toll that 44 years of incarceration as a political prisoner took on his body, Eddie had to stay remote during our time as colleagues. And even though we worked together every day, it was always through a screen. But, my God, I will always cherish those moments we got to share, or moments I simply got to witness, in those contexts. I got to see Eddie’s serious, stoic face melt into a smile when his dog Chunky ran in the room and interrupted a Zoom call. I got to hear him talk with a general’s precision about what stories we needed to cover on Rattling the Bars and why. But I think my favorite memories will always be the calls Eddie took on his porch, in his hanging chair, even when it was freezing-ass cold outside. I would glance down at my screen and see him listening to the call while looking off to the side, free, in the open air, looking out at the trees and street and cars with all the adoration and quiet gratitude of a child seeing the ocean for the first time, or of an elder seeing it for perhaps the last time…

I’ve spent much of the past year regretting all the conversations Eddie and I didn’t get to have (during our time as colleagues, we only published one conversation together). I still lament the time that was stolen from us, and I know I always will, but today I am grateful… “Many people see me only through a political lens,” Eddie wrote in his autobiography, which he coauthored from prison with his indomitable wife and fellow freedom fighter Dominque, “but I am a human being, with very human relationships.” Even though the most childish, self-pitying part of my heart is still upset about the questions I can no longer ask him myself, all the things I wanted to learn about him, I am so filled with gratitude that, before and after his passing, I have gotten to know Eddie better through those human relationships, by talking to the people whose lives he also touched—and he touched so, so many people’s lives. The world is in a dismal state, but it would be a lot worse off if we had never been blessed with Eddie’s light. I know that much.

The great Vassily Grossman once wrote:

“I have seen that it is not man who is impotent in the struggle against evil, but the power of evil that is impotent in the struggle against man. The powerlessness of kindness, of senseless kindness, is the secret of its immortality. It can never be conquered. The more stupid, the more senseless, the more helpless it may seem, the vaster it is. Evil is impotent before it. The prophets, religious teachers, reformers, social and political leaders are impotent before it. This dumb, blind love is man’s meaning. Human history is not the battle of good struggling to overcome evil. It is a battle fought by a great evil, struggling to crush a small kernel of human kindness. But if what is human in human beings has not been destroyed even now, then evil will never conquer.”

He was the best in all of us, the embodiment of everything that makes humans worth a damn, an awe-inspiring example of the most inextinguishable part of the human will and what horrors a person can endure in the fight to be free.

Anyone who knew Eddie knows that he was living proof of this. He was the best in all of us, the embodiment of everything that makes humans worth a damn, an awe-inspiring example of the most inextinguishable part of the human will and what horrors a person can endure in the fight to be free.

I will never lose faith in what humanity can be, in the world we can still build, because I knew Eddie Conway.