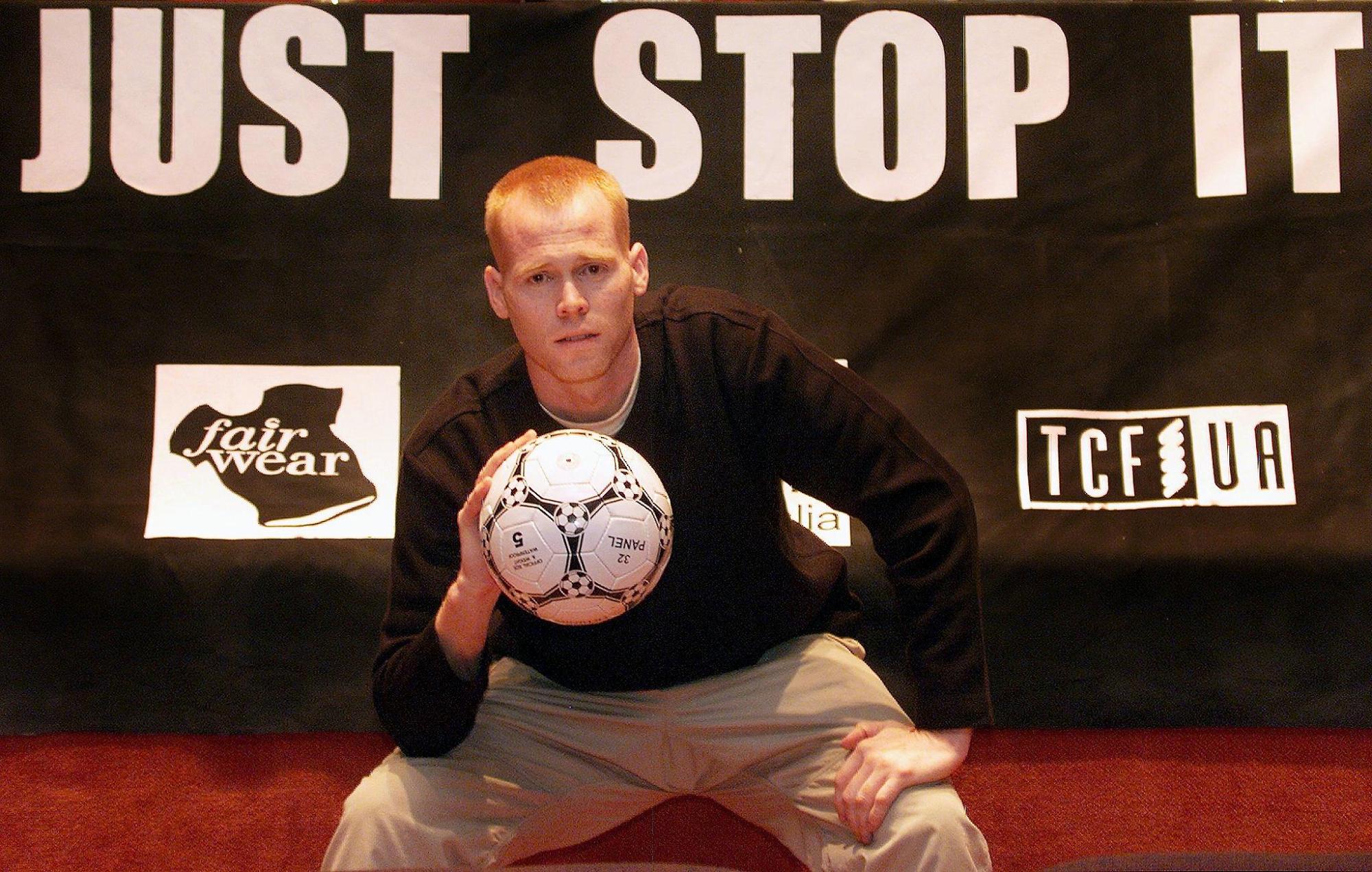

Edge of Sports is back! In this Season 2 premiere, former St. John’s University Assistant Soccer Coach Jim Keady joins Dave Zirin to talk about why he left college coaching in protest of Nike sweatshop labor. He then spent a month in Indonesia exposing the company’s sweatshop abuses, making the film “Behind the Swoosh.” We also discuss the recent film “Air,” about Nike’s relationship with Michael Jordan, and the ways Hollywood is whitewashing Nike’s sins.

Studio Production: David Hebden, Cameron Granadino

Post-Production: Taylor Hebden

Audio Post-Production: David Hebden

Opening Sequence: Cameron Granadino

Music by: Eze Jackson & Carlos Guillen

Transcript

The following is a rushed transcript and may contain errors. A proofread version will be made available as soon as possible.

Dave Zirin:

A division one coach who said no to Nike over sweatshop abuses, women in mixed martial arts, and a return to racist mascotting in D.C.? Oh, hell no. It’s season two, on Edge of Sports.

(singing)

Welcome to season two of Edge of Sports, here on the Real News Network. I’m Dave Zirin, and today we speak to Jim Keady, who as a division one soccer coach said no to wearing Nike gear in protest of their sweatshop abuses and paid for it with his job. That led him to Indonesia, where he lived with Nike factory workers to document their struggles in an award-winning short documentary called Behind the Swoosh. And we have much to discuss, including the recent film air and whether it was an exercise in what I’m calling Nikeganda. Also, I’ve got some choice words about a push to change the D.C. football name back to a racial slur. And on Ask a Sports Scholar, we speak to Professor Jen McClearen about her work examining the role of women in the world of ultimate fighting. But first, Jim Keady. Jim, thanks so much for joining us on the show.

Jim Keady:

David, it is a pleasure to be here. It’s always great to see you.

Dave Zirin:

I gave the audience already a thumbnail of your history with Nike, but let me cue you up so you can talk about it, of course, in your own words, you’re coaching soccer, your great sporting love, you’re at St. John’s. And then what happens?

Jim Keady:

In the late nineties, 1997, I was coaching at St. John’s University in New York City. At the time, we were the NCAA division one defending national champions with the best team in the nation. I was brought in to train the goalkeepers for the program. And while I was coaching, I was also pursuing a master’s degree in theology. I had been a high school religion teacher prior to going up to St. John’s and wanted to continue my studies in that area. And in my first class, Moral Person, Moral Society, I was encouraged by my professor to find a paper topic that was linking moral theology in sports to things that he saw I had a passion for. So I decided really on a whim to look at the Nike Corporation in light of what’s called Catholic Social Teaching. And what I found was if you wanted to pick a company that completely violated everything we claim to stand for as the largest Catholic university in the world, Nike was it.

And at the same time that I’m learning about how Nike’s exploiting their workers and not paying living wages and union busting and violating basic worker rights, over in athletics, we’re negotiating a three and a half million dollars endorsement deal with Nike. And part of that deal would require me as a coach to wear and promote the products. I took issue with this. I approached my head coach, the athletic director, anybody that would listen, eventually administration to university saying I did not want to personally be a walking billboard for a company that was exploiting people in developing countries around the world. And I didn’t think that as a Catholic institution we should be taking three and a half million dollars of endorsement money that was really taken from the mouths of the workers who produced the gear that we were all wearing as athletes. And I tried to negotiate myself out of this deal personally, behind the scenes, for about a year.

And eventually I was given an ultimatum by my head coach, “You’ll wear Nike, you will drop this issue or you resign. End of story.” And I held my ground and I was forced to resign. I became the first, and I’m still the only athlete in the world to say no to Nike because of the sweatshop issue. And that made big news. That’s when that issue first started to explode into the mainstream consciousness of American consumers. And I was now this instant expert on the issue: I’m getting invited onto radio programs and to college campuses to talk about the issue and journalists are interviewing me. As I’m doing these lectures on these college campuses, I had the market fundamentalists in the business school and the school of economics challenging me saying, “You don’t know what you’re talking about. Those are great jobs for those people. This is how development works. What else would they be doing?”

I knew their neoliberal development model and arguments were a sham. The competitive athlete in me wanted to prove them wrong. So in the summer of 2000, I put a project together and I moved to Tangerang, Indonesia, this industrial suburb outside of the capital of Jakarta, and for one month tried to live like a Nike factory worker. I tried to survive on their wage. At the time, it was $1.25 a day, and lived in a rat infested slum with open sewers surrounding the place that I lived and sleeping on a thin mat on a cement floor ain a really hot and humid room. I lost 25 pounds that month and met the workers, mostly young women, who made the stuff that I wore for my entire life as an athlete.

Prior to me writing that research paper, I never thought twice about who made my gear. I just wore it. And I wanted the best gear like every athlete does, and was duped into thinking that somehow that’s going to make me a better athlete by having a certain logo on my chest or on my sneakers. I promised these workers that I would go home and I would tell their stories, and I thought I was going to do a six or seven week speaking tours from universities. And the first year that I was home, I was on the road for seven months. I spoke at more than 80 schools and saw there was an incredible hunger for this kind of grassroots education, particularly on this issue. And I founded a nonprofit organization back then called Educating for Justice to facilitate me continuing to do that work. And for nearly 15 years, I went back and forth to Indonesia and I would gather new information.

Unfortunately, there was always a bad story that had to be told whenever I went there. The pervasive issues of paying poverty wages, union busting, not respecting workers’ rights to freely associate to form those trade unions, Nike refusing to collectively bargain with workers and their trade unions, those have consistently remained the same. And there were other issues that would just pop over the years. I did a lot of good work in raising awareness and it’s a story that continues to need to be told because it’s still happening today. I get messages from workers on the regular. I’m now because of social media, can be connected with people in a way that I was not able to be connected with going back into the late nineties and early aughts. So that really helps facilitate the information sharing.

Workers are still paid a poverty wage. They still have issues with union busting, particularly through COVID where there was a lot of illegal layoffs. And I know companies had to lay off people. I’m certainly sympathetic to what was happening, but there’s a process as per, using Indonesia as an example, the Indonesian labor laws that are supposed to be followed. And it was not. These workers were really left high and dry and in a time period where yes, Nike saw a short-lived contraction when COVID hit, and then exploded again. They’re making more money than ever right now and certainly could afford to take care of those workers who helped build the entire Nike success story.

Dave Zirin:

Wow. Well, is this about the apparel industry or is this about Nike? Are there other apparel companies that do it better? Is Nike appreciably worse? How do you understand that?

Jim Keady:

Nike’s the industry leader and our strategy, my strategy has always been to… And it wasn’t like I sought out Nike to do this activist work. I was writing a research paper, that’s why I always caution students, “Be really careful of what you pick for a paper topic when you’re in college, because you never know what kind of odyssey it might lead you on.” So it turned out that I was looking at the industry leader, and as the leader goes, so the industry follows. But to be clear, I’ve interviewed workers that produced for Nike, Adidas, Reebok, The Gap, Old Navy, Tommy Hilfiger, Polo Ralph Lauren, Lotto Field, Levi’s, Puma, ASICS, [inaudible 00:08:58], New Balance, Converse. I have colleagues that have interviewed workers that produce for FUBU, Phat Farm, Timberland, J. Crew, Macy’s, Abercrombie. And 90 to 95% of the close in shoes that are bought and sold in the US domestic market and around the world are made in sweatshop conditions.

So we were looking at one company, Nike, in one country, Indonesia, to try and create a model for change. And if we could win some real gains for workers with Nike in Indonesia, then we could move from Indonesia, China to Vietnam, Vietnam to Honduras, Honduras to El Salvador, these dozens of countries where Nike operates. And then you could go from Nike to Adidas, Adidas to Reebok, Reebok to The Gap. Then you could go from apparel and footwear to toys, stuff that we’re buying at Christmas for our kids or during the holidays for kids or birthdays. We could go from toys to electronics. All the equipment that we’re using to have this conversation right now, made in sweatshops. We could go from electronics to houseware, stuff that everybody’s buying at Kmart and Walmart and Target and Kohl’s. And what we would start to do is build a global labor movement that would balance off the globalization of capital that has gobbled up countries, communities, and in some instances countries, all in the pursuit of maximizing profits for absentee owners, also known as shareholders.

Dave Zirin:

Now Jim, we often speak about sweatshop workers, particularly in Southeast Asia, as victims. But can you speak about what you have seen in terms of resistance, how people in these communities resist these conditions?

Jim Keady:

Absolutely. It is not dissimilar from the resistance stories that we saw in the American labor movement. You have people who are willing at times to literally put their life on the line. And off to my left here on the wall, I have a poster of Marsina. Marsina is a martyr, a labor advocate in Indonesia who was pushing the envelope for labor rights and was eventually found in a ditch, murdered. I’ve interviewed workers who have been threatened at gunpoint, threatened at knife point, beaten with machetes, and they still continue to step into that breach and say, “We are human beings, we’re not machines. We have dignity. And we’ll demand that that dignity be protected and respected.” And what they need… Now look, if this were an Indonesian versus Indonesian fight, then we might say as Americans, “All right, not our business.” But these are Indonesian workers who are up against an American transnational corporation that has entered their country as a neo-colonializing force and they need our help.

There’s been countless conversations that I’ve had with workers where I laugh and not… It’s just like, god, they’re thinking in a very Indonesian way, and I don’t mean that in any way to disparage them. They think very communally. They’re concerned more about, again, the community, the campoon, the village, each other. And I would have to stop them and say, “Ladies and gentlemen, you are up against a cutthroat American capitalist corporation whose values are grounded in some of the worst examples of American competitive spirit. And believe me, I know it. I grew up as an American athlete,” and helping them to develop the mindset and the tactics to fight back against this American colonializing force that has taken over communities.

And in the case of Vietnam where they… Indonesia, Vietnam and China are the three main hubs for the sneaker production. A number of years back, and I haven’t checked of late, but I would be surprised if this changed, Nike was the largest private employer in Vietnam.

Dave Zirin:

Wow.

Jim Keady:

So you think about that and the amount of leverage that gives them with the Vietnamese government, with officials from every level of government, as well as any of the crony capitalists that are working that system within Vietnam or China or Indonesia.

Dave Zirin:

Stunning. So we’d be remiss if we didn’t talk about the film Air, Matt Damon, Ben Affleck, it came out a few months back. It chronicled Nike’s creation of the Air Jordan sneaker and the signing of Michael Jordan. It includes numerous Oscar winners, it got great reviews. Basically, it was a prestige production about a shoe. Is this Nikeganda?

Jim Keady:

Yes. I was incredibly disappointed as someone who is a huge fan of Ben Affleck and Matt Damon as filmmakers. I mean, Goodwill Hunting still ranks in my top five. I still cry every time I watch that movie. And these are guys who have a social conscience. They’re aware of critical issues, and they missed a tremendous opportunity to sow that into this film. Now look, as a guy who grew up playing basketball, came of age in the mid to late eighties, I graduated high school in 1989, just the opening scene of the film and all that cross playing and all the cultural references, I loved it. My seventh grade self in 1984 was like, “This is awesome.” But my 51-year-old self who’s been pushing back against Nike’s labor abuses for the last 24 years, 25 years was really, as I said, just disappointed.

They had one fleeting mention of the labor issues. Jason Bateman’s character says something late in the film, and it was almost like a non-sequitur, like they jammed it in to maybe say, “Well, we talked about it a little bit.” But to talk about the creation of the Nike success story, to talk about the creation of what would become the Jordan brand and the Jumpman brand, and not talk about these labor issues that were… This was an international news story for a year solid where a lot of people were paying attention and to not have that as part of this…

And they featured Sonny Vaccaro as one of the protagonists in the film. And any kid who grew up in New Jersey playing basketball in the mid to late eighties in high school knew who Sonny Vaccaro was. Sonny’s no angel. I mean, look, he’s done an incredible amount for the game. He has certainly help individual players maximize their branding ability and these kinds of contracts. I certainly can give them that from a sports and business perspective, but Sonny was also pushing these endorsement deals, and where did that money come from? That money came from the mouths of workers in places like China and Indonesia and Vietnam.

From the work that I’ve done over this over the years, I have a bunch of archival news footage and one of the news stories that I have, there’s footage of Sonny talking about the endorsement deals and when he first started to cut them with the colleges, the universities. And he said something to the effect of, “I knew I could get them to sell their souls. Surprised at how cheaply they were willing to do it for.”

And it’s something that I’ve said that every university, and I’ve lectured at more than 500 schools in 43 states around the US and asking that question where these endorsement deals, and I’ve been at schools where there are massive endorsement contracts with Nike and asking, was that enough? If we’re just looking at this from a pure business perspective, what is the name, logo, reputation, and history of St. John’s University worth to hock products for Nike?

This is before I became persona non gro in the athletic department, I’ve got memos, one of which was detailing we were one of the three schools in the country that will be the launch of the Jordan brand. This is why they wanted St. John’s in particular, because of the basketball program and the history with carne seca and the story Big East Program at St. John’s was. And because we were in the largest media market in the United States. And now to have the men’s soccer program win the national championship? And every other program in the athletic department at that time was wearing Nike except soccer. We were wearing Umbro. So the full court press was on. That was the linchpin of it. And again, the memo said something to the effect of, “Sprinkle in a little bit of that New York vibe and with St. John’s history, and we will serve the Jordan brand up to the masses.”

Dave Zirin:

Oh, man.

Jim Keady:

That’s what the largest Catholic university in the United States is supposed to be doing? We should be serving up, from a faith perspective, serving up Jesus good news to the poor, to the masses.

Dave Zirin:

Just one more question about Air to go back to it, because the depiction of Phil Knight, and I was hoping you could speak about the founder of Nike and perhaps the gap between the Phil Knight in the movie played by Ben Affleck and who Phil Knight really is.

Jim Keady:

Sure.I can’t say who Phil Knight really is in reality. My interactions with Phil had been fleeting. I had one flashpoint moment where I met him on Nike’s campus and invited him to come to Indonesia with me and meet workers. And if people want to see that, just Google Jim Keady, Nike, ESPN, because ESPN aired. I had it filmed, my partners with me at the time, and we filmed this whole interaction with Phil. So I’d encourage people to take a look at that. And my other interaction with Phil was when he illegally ended a Nike shareholder meeting in 2002 and had me escorted out by the Portland Police when I was pushing the envelope and demanding answers to questions about their labor rights stuff. And Phil Knight is a cutthroat capitalist, I would say borders on sociopathic with regard to the drive to make money.

And in the film he’s presented as kind of this just affable business guy who’s willing to take some chances and push back. Kind of the classic jock mentality, the banter back and forth, that hard edge and who’s going to win in this argument, and then eventually conceding to Vaccaro and say, “Yeah, let’s go for it.” And there’s this whole other part of him that the Nike model, when Phil wrote his paper when he was an MBA student at Stanford University, the crux of his MBA thesis was that he was going to exploit cheap labor in Asia, take the cost savings, pump it into promotions, advertising, branding, and marketing, and build this behemoth.

That model is now the model for every major apparel and shoe company. And Nike led the way, and Phil, he’s been the captain of that ship in exploiting. Like the colonialists before him, going to places where they could exploit human beings, they could exploit the environment, they could exploit dictatorial governments and create partnerships with them to exploit the environment and a labor force. Phil Knight is no different than the brutal colonists that came before him for hundreds and hundreds of years.

Dave Zirin:

Given everything you’ve told us, the fact that the right wing in the United States has decided to say that Nike is the woke company because of associations with people like Colin Kaepernick, I just have to know, does a vein burst in your head when you hear the right try to cast Nike as this kind of woke, progressive champion given everything you know?

Jim Keady:

It’s understandable. Yes, I get wildly frustrated and I wish I had as many platforms like this as I could get on to talk about these issues and help to educate people. I try not to demonize people out of the gate. You can only be responsible for what you know, so they may not be aware of the bigger picture of Nike. And the only reason that Nike is attempting to be woke on any issue is because it’s good for their bottom line. So they’re making a calculation in the boardroom and saying, “Hey, if we place our bet on this issue, what is the data telling us? That hey, this is our market share with this particular demographic. This is where the future is. This is where sneaker and apparel sales will be made. Here’s who we need to back in any given instance.”

Those decisions are not made of a grounded philosophical or theological conscience that is really deeply concerned about what these political, social and economic issues are driving at and these movements are driving at to create change and justice. It’s interesting. Along these lines, Jonathan Isaac has launched his new brand, UNITUS and billing it as a Christian brand. And I’m interested to see where he is going to produce his stuff.

Dave Zirin:

He’s calling it faith and freedom shoes, but where is he producing this faith and freedom?

Jim Keady:

Yes, and again, I’m open, willing to give him the benefit of the doubt. I did hear from a colleague of mine that he had said, and this is hearsay, that they were going to produce in Vietnam. Let’s just say hypothetically they are. Well, that’s problematic on the freedom component because in Vietnam it’s illegal to freely associate and potentially form trade unions and have those unions bargained with. So if he were to say, “Hey, I know that and I’m intentionally going in there and here’s my five-year plan to try to break that open and create political freedom for workers,” okay, I’d be willing to give him five years to see if he could make that happen. And then have a hard stop where, nope, we’re out of here because this isn’t happening.

Right out of the gate, the language is, again, as a Catholic, I can say, “Okay, someone wants to build a company that’s grounded in their religious values. I’m okay with that, but can you really walk your talk or is it just going to be flowery window dressing no different than what Nike is being accused of on the woke side? Where Nike’s hedging a bet and leaning into the woke stuff, which let me be clear, woke stuff isn’t bad. It means you’re awakened. You’re awakened to racial justice, political injustice. Go through the laundry list of issues that one gets awakened to. You’re not walking your talk in terms of your political activism and really pushing on the root cause of the issues that are creating the injustice. It’s just whitewashing, greenwashing, social justice washing, whatever you want to call it, but it’s not authentic.”

Dave Zirin:

No way. Jim, you’ve been terrific. Last question. How can people keep up with you in your work?

Jim Keady:

Sure. I encourage people to follow me on Twitter or whatever it’s being called, X, I guess, and it’s at J-W-K-E-A-D-Y, J-W-K-E-A-D-Y, jwkeady. Also under that same handle on Instagram, and certainly on Facebook, people can find me. Just look for Jim Keady and this face in the profile picture, and I would love to hear people’s feedback. Critical feedback, positive feedback, whatever it might be. I’m certainly always open to a conversation, and if there’s any blind spots that I have as I’m discussing this issue. Certainly open to having people point those out because we’re should always be in the position where we want to learn and deepen our understanding on issues so that we can go out into the trenches and be better activists and advocates and help alleviate the suffering in the world for people that are struggling and in need of justice.

Dave Zirin:

Jim Keady, thanks so much for joining us on Edge of Sports TV. Really appreciate it, man.

Jim Keady:

You got it, Dave. Always great to see you.

Dave Zirin:

And now for some choice words, 20,000 people. That’s the number that have signed a petition calling for the NFL’s Washington Commanders to change their name back to the dictionary defined racial slur that branded the franchise for decades: Redskins. This is a word I normally do not utter, but in this context, I think it is important to feel the weight of the violence of the word. A word which derives from the scalping of Native Americans by professional bounty hunters. Bounty hunters who are paid per red skin. Now I get why people want the old name back. It’s associated for many, not with racist violence, but with Super Bowls and the glory days. And yes, the name Commanders really, to use an academic term, sucks. It really sucks. It’s awful. It sounds like something conjured by a marketing exec who uses words like synergy. It doesn’t make you think of the city or of Gridiron Glory. The only image it conjures is Russell Crowe in a puffy shirt and a ponytail.

I also get that people associate the commander’s name change with the person who until last month held the title of the most disgusting franchise owner in sports, Dan Snyder. The odious Snyder dragged this team through 25 years of scandal, bigotry and football irrelevancy. So I understand why diehards, now that he has sold the team, want to turn the page. But before looking backwards for a new name, let’s be clear about the facts. The fact is that the repugnant Snyder was the champion of the old name and only changed it because of grassroots pressure led by Native American youth as well as a mighty push from team sponsors who demanded that it change following the police murder of George Floyd.

But now, like a horror movie villain rising from the dead, the name is straining to come back. And I’m not surprised at all. This is 2023, not 2020, and the politics of reaction are rampaging the landscape. Even this meager victory from the summer of 2020, the changing of a football team’s name is now as endangered as all those corporate diversity jobs so in Vogue three years ago. So you get state curriculum now that makes slavery sound like a trade school, you get Tony Morrison banned from libraries, and you get a howl to fight the woke mind virus by returning the racial slur back to its position of acceptance and prominence.

So before we slouch back into performative white supremacy, let’s remember a few things: Let’s remember that every tribal council in the United States from the Chippewa to the Cree had asked, to Snyder’s deaf ears, that the team name change. Let us remember that the name only exists because the first owner of the team was a stone-cold racist named George Preston Marshall, who was an arch segregationist that made sure the team was the last in the NFL to integrate. Marshall, who was elected into the Pro Football Hall of Fame had a deep affection for the Slave South and minstrel shows. And for years, he had Dixie played before home games. In fact, the iconic fight for old D.C. Washington football fight song under Marshall’s watchful eye used to go not fight for old D.C., but fight for old Dixie.

Let us remember, it’s a racist name coined by a racist man, and it belongs nowhere but the dust bin of history. So to everyone celebrating the end of Daniel Snyder, I am with you! To everyone who wants the name to not be the Commanders, I am with you! But to everyone who in a fit of joy over Snyder’s departure wants to go back to the old name, I just have to say, stop it. This team has a championship past and the name is a jagged scar on that history. No other team would call themselves a racial slur, and it is the mass extermination of the lives of indigenous peoples that created the preconditions for such a vile brand. So to put it simply, if your team needed a genocide to come up with its name, then it’s probably time to get a new name.

And now in our segment, Ask a Sports Scholar, we have the author of the book Fighting Visibility: Sports Media and Female Athletes in the UFC from the University of Texas, professor Jennifer McLaren. How are you, professor?

Jennifer McClearen:

I’m doing well. Thank you for having me today.

Dave Zirin:

Thrilled to have you on. So first and foremost, it’s such an interesting area of research. What brought you to the women of the UFC?

Jennifer McClearen:

I was in grad school around the time that they first introduced women into the UFC. This is back in 2012, and I had just started watching UFC for maybe the year prior because I was training Brazilian jujitsu and a lot of people in the Brazilian jujitsu community watch MMA, and so my friends kind of got me into it. And I was in a grad program in media studies and I was interested in gender and representation in the media, and it seemed like a really good opportunity to get in early on a topic that nobody was really thinking or writing about because they introduced women into the UFC after saying for 20 years, “Never, never, never. We’re never going to introduce women into this organization.”

And they did. And I was a little skeptical at first because I thought, are they going to actually really give it a go? Are they going to not treat women in the same way in terms of production, how they would men? And I was kind of pleasantly surprised and intrigued, and that’s what started this sort of several year investigation of what was actually happening in the organization when they introduced women and how they kind of folded female athletes in.

Dave Zirin:

I find the title of the book so interesting. You might think that given the subject matter it would be called Fighting Invisibility, and you call it Fighting Visibility. Why that choice?

Jennifer McClearen:

It was a very purposeful choice because for so long in the research on women’s sports, it has been about increasing representation. Women are broadly underrepresented in sports media culture. We know this. Somewhere between 4 and 10% of all sports media coverage worldwide is of women’s sports. So we know overall it’s abysmal. And then secondly, when women are portrayed in sports media, oftentimes it’s not done at the same level or is not done without a lot of stereotypical types of representation where we focus in on certain tropes of female athletes. And so that has been the force of the research and the cultural discourse: We need more representation, we need better representation.

So I started from the standpoint that what if we looked at what an organization was doing well in terms of representation, but then kind of flipped it a little bit and said, is that enough? Is that actually going to give us the equity that we are seeking in women’s sports or is it doing other things? And what I found through researching this book and writing this book is it became the representation of the empowered female athlete in the UFC. Became this seductive mirage for progress, when actually, if you look behind the curtain, all fighters in the UFC are exploited and that they’re not paid well, and women are bearing the brunt of a lot of that inequity. And so I really wanted to question what visibility actually gets us if women aren’t being fairly compensated for their visibility. If the organization is making all the money off that visibility and the athletes themselves aren’t, then does representation really matter as much as we tend to think it does in society?

Dave Zirin:

So many sports that are of a combat nature that introduced women late always seem to start by accentuating heteronormative women and a heteronormative gaze. I’m thinking of everything from foxy boxing to World Wrestling Entertainment. How does the UFC do in terms of presenting real women as real fighters and not as an adornment to the product?

Jennifer McClearen:

That’s a very interesting question because I think UFC has done quite a few different things with representation. So I wouldn’t say they get too far away with your headlining fighters. If you look at Rhonda Rousey, it’s not that they ignored the fact that she was also conventionally attractive. They definitely played that up as part of how they represented her. But they got really interested in the cultural discourse around women’s empowerment in the mid 2010s. So this is really at the height of Rhonda Rousey’s fame. And what they found out is it surprised them that Rousey was actually more popular with female fans than with male fans. And they realized that they had an ability to kind of tap into a female fan audience and draw them into the sport. And so they started thinking about how they could represent women differently, and that is kind of telling more authentic stories, trying to bring in stories of women defying the odds and overcoming challenges within a male dominated sport.

It was really quite interesting to see that happen in a sport that was once called human cockfighting. And that was notoriously for so many years, had this reputation of being entirely too brutal and uncouth and still has that to a degree, I would say, today. But they really wanted to focus in because they realized that they had an untapped demographic. And that’s what the UFC has been doing for a long time, is they’ve been trying to expand into new markets.

They do that internationally. So they try to fixate on a particular fighter from a region, so Connor McGregor in Europe or Jingliang Li in China, and really market that fighter in that region in order to draw more audiences to the sport. They did the same thing with Latin America and trying to bring in more audiences from the Latinx demographic, and then they did it with women too. So I think, in a lot of ways, you could look at it as successful marketing for sports in that they actually thought, what do female fans want in seeing representations of athletes, which is not generally the starting point for most sports.

Dave Zirin:

Dana White, the, I guess we’ll call him war chief of UFC, a Trumpist, someone who was caught on camera hitting his partner. I mean, this is not a good person, not a future guest on Edge of Sports TV unless it’s super argumentative, which I’m open to. But does he deserve any credit though for this, or is this much more about the emergence of an audience and the emergence of these fighters?

Jennifer McClearen:

That’s a complicated question. So I would say that when talking to people, I talked to marketing folks in the UFC and I talked to different people working, and I would say they deserve more credit than he did in terms of actually figuring out what was happening in terms of how to market the sport to women. I think he takes a lot of credit because he was the guy that gave Rhonda Rousey a shot, and he said that it was going to be a six-month experiment, and he was very skeptical that it was going to do anything. But because of the star power of Rhonda Rousey, it exceeded expectations. And there was a while there that she was the highest paid UFC athlete, which kind of shocked the organization.

I don’t think we can give him too much credit because he basically realized what fans and scholars of women’s sports for a long time have said, is if you invest in women, if you actually give them a shot and you put them on pay-per-views and you put them out in the world and at the production value level that you do with men, you can sell the sport. And so he kind of happened upon that and went with it, whereas if we were doing a case study of the business, we could point to it and say he actually wasn’t stubborn and read the numbers and actually invested.

But of course, Dana White, there’s a lot we can criticize about how he leads that particular organization and some of the symbolic representation he has in terms of his connections with Trump and all of that. So I don’t want to give him too much credit overall, but it is interesting. But I think that what it tells us is that women’s sports is a marketable product if done right and not seen as just a charity, which is something that we look at a lot. A lot of owners of women’s sports teams kind of think of it as this community service that they do, not as an actual investment. And I think that that’s the real difference, and that makes a difference in the actual product, of course.

Dave Zirin:

It’s so interesting. We spent the first part of this show talking about Nike and the gap between representation and their labor practices and how can we speak about them elevating marginalized groups if they’re oppressing a lot of those same groups for the purposes of producing their shoes and their apparel. This feels very similar in what we’re talking about.

Jennifer McClearen:

Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. And I’ve written a little bit about that connection, in fact. In looking at some of the representation that Nike had, they had a commercial during Black History Month a couple of years ago that was really focusing in on Black female athletes. And it’s a really inspiring commercial that really connects with Black women in the audience. It’s a powerful representation, and that’s really the heart of the argument of my book is that there’s so much cultural cache in representation matters. There’s so much cultural cache in if she can see it, she can be it. Because there’s this emotional connection that we have with ads.

There’s this emotional connection that we have with representation, especially if we come from marginalized groups like women athletes or fans of women’s sports where we’re not used to seeing it at the same level as men. And the first time we see it, it’s an incredibly powerful experience, and I don’t want to knock that experience because it does matter to people. Those feelings are real, and I don’t want to downplay that too much. But what we have to then look at is what is actually happening in that company, in that organization? Are they practicing what they preach? And in the case of Nike, they have not. Historically, they’ve had really terrible labor practices, which I think they have improved some in recent years because of the scrutiny they’re under. But across the board, if you look at their representation of gender and difference across the board, it doesn’t compare to their actual practices. And this is the exact same thing that I was seeing in the UFC.

Dave Zirin:

Wow. We speak a lot about trans issues in sports on our program, so I’ll lay it out to you. Trans women, trans people, non-binary people in ultimate fighting. What have we seen? What do you think we will see in the future?

Jennifer McClearen:

I’ve actually written about this topic as well. So one of my first pieces that I ever wrote about MMA was looking at the fighter Fallon Fox, who was an active fighter, again around the 2012, 2013 period of time. And she wasn’t in the UFC, she was in a professional league, but she wasn’t in the UFC. And she experienced an I intense amount of vitriol and scrutiny. I think obviously combat sports in particular, because there’s physical combat between two bodies, that’s one space that is really difficult for a lot of naysayers around transports or trans people participating in sports. And so I think it’s going to be probably, unfortunately, a long time before we make progress in the area of actually seeing trans fighters at higher levels of promotions in MMA. I think that there’s more room, probably initially, in sports that don’t include physical contact with the other person’s body.

It’s something that I write about and think about a lot. I think a lot of what happens that, there was an article that I wrote recently that looks at this discourse that’s happening in our society around trans athletes in particular, focuses in on adultifying trans girls and posing them as some sort of threat to cis female bodies, but then it also infantilizes cis women in the process because there is this way that we talk about protecting them in society. And if you look at all the legislation in the state legislatures right now or in more recent period of time, there’s a lot of focus on, well, we must protect our daughters, even if they’re talking about adult women, even if they’re talking about collegiate sports. And so I think there’s this duality between the adultification of trans girls and the infantilization of cis women athletes.

Dave Zirin:

Wow. Just one last question. You’ve been so generous with your time. You’re a professor, you speak to a lot of young people about these issues. Where do you find the generation of people you’re speaking to? Where do they fall on the questions of trans inclusion? Are they sympathetic to it? Are they against marginalization? I’m, of course, assuming most of your students are cisgender. What are they saying? What’s their common sense response to this debate?

Jennifer McClearen:

I have said for a long time that Gen Z is going to change the world because when talking with my students in the classroom, I have a lot of hope actually for issues of gender and race and diversity more broadly in general, because they seem to be much more aware. I’ve been teaching at the University of Texas for the past six years, and when I first came in, I had to be a little bit more basic in talking about things like gender identity and the differences between sex and gender and all of those things. And now I’ve had to kind of revise how I even introduce those topics because they’re so much more savvy, they’re so much more aware. There’s so many more students that come in that identify as non-binary or sexually diverse in some other ways they identify, in different ways.

And so they’re actually quite perplexed a lot of times when we start talking about some of these issues around trans athletes because they don’t understand why so many people are viewing these issues in these very binary sort of ways or essentialized sort of ways. So they actually give me a lot of hope. And I think every time I teach the class, I teach a class on women in sports media, and every time I teach that class, I come away feeling more hopeful for the future of women’s sports, for sure.

Dave Zirin:

Amazing. I can’t help but ask this as one last question. Are you concerned at all between the gap of the politics of your students and what the state government is doing in terms of trying to constrict what you and others can teach?

Jennifer McClearen:

Oh, absolutely. This is highly concerning and something that I’ve been thinking and talking a lot about in recent years. Obviously, I work at the University of Texas, which is funded through the state legislature of Texas and the regents and the governor and the legislature has a lot of power over us as an institution, and they’ve only increased that with the most recent legislative session. And so I’m really interested to go into the classroom in the fall and see how the students are responding to that because they’re very much coming from a very different place. And I think, again, I’m hopeful for the state of Texas even because I think that with this generation, a lot of things could change, and I’m really hopeful that eventually we’ll see a more balanced state legislature or even a democratic state legislature if these students start coming into more political power or start having more voice in the politics of the state. I hope that my hope is well-placed, but I do maintain that, for sure.

Dave Zirin:

Wow. Will you come back on the show at the end of the semester and tell us what you learned?

Jennifer McClearen:

Absolutely. I would love to.

Dave Zirin:

I’m so curious. I’m so curious what that’s going to be like. How can people keep up with you, professor?

Jennifer McClearen:

Sure. I’m on Twitter at jmcclearen. That’s M-C-C-L-E-A-R-E-N. You can find me there.

Dave Zirin:

Awesome. Thank you so much for joining us on Edge of Sports TV. Really appreciate it.

Jennifer McClearen:

Thanks for having me.

Dave Zirin:

Well, that’s all we have for this week’s program. I’m so glad to be back here on season two here at the Real News Network. Thank you so much to everybody at TRNN. Thank you to everybody out there watching. You could always reach me, Dave Zirin over whatever Elon Musk’s ex-Twitter thing is at edgeofsports. For everybody out there listening, please stay frosty. We are out of here. Peace.

Outro:

Thank you so much for watching The Real News Network, where we lift up the voices, stories and struggles that you care about most, and we need your help to keep doing this work. So please tap your screen now, subscribe and donate to the Real News Network. Solidarity forever.